Chant Down Babylon: Building Relationship, Leadership and Power in the Food Movement

The following is an excerpt, reprinted with permission, from Chant Down Babylon: Building Relationship, Leadership, and Power in the Food Justice Movement published by WhyHunger.

In September 2013, three grassroots organizations – People’s Grocery (Oakland, CA), the Social Justice Learning Institute (Inglewood, CA), and the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network (Detroit, MI) – convened in Detroit to initiate a conversation and develop action around collective leadership by people of color in the food justice movement. The executive directors of all three organizations have worked with and inspired WhyHunger in various ways over the years, and agreed to take the opportunity to participate in the Food Justice Voices series.

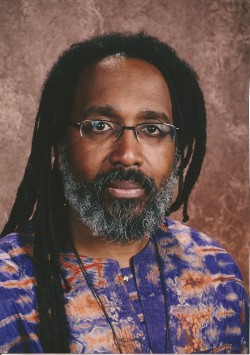

Malik Yakini is the Executive Director of the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network and a Food First board member. D’Artagnan Scorza, PhD, is the Executive Director of the Social Justice Learning Institute in Inglewood, CA. Nikki Silvestri is a Social Innovation Strategist and former Executive Director of People’s Grocery in Oakland, CA and a Food First board member.

MALIK: I think one of the unique things that people of African descent bring to this work is the spiritual approach that we have relating to the land, and also to farming and food. And you know within both traditional African systems, and systems that were created and adopted by ancestors in this country, this kind of sense of spirituality really permeates how we move through the world. So I think, really, that’s one of the strengths we bring, not only to the food movement, but I think it’s one of the strengths that we bring to humanity, as well.

NIKKI: One of the conversations D’Artagnan and I got into was about people of African descent, and how the rhythm that we carry in our blood is intimidating for people because it awakens things that are really uncomfortable. It awakens the primal, and the visceral, and the deep.

NIKKI: One of the conversations D’Artagnan and I got into was about people of African descent, and how the rhythm that we carry in our blood is intimidating for people because it awakens things that are really uncomfortable. It awakens the primal, and the visceral, and the deep.

D’ARTAGNAN: Those are experiences and forms of expression that people are not comfortable with, right? You know, it makes me think back to my time on the UC Board of Regents. When I served on the board it took me a while to adjust to the environment. And, you know, in the first four months everyone thought I was an angry black man.

NIKKI: For real? They thought you were an angry black man?

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

Sign up today!D’ARTAGNAN: Oh yeah. Yeah. Because I spoke with passion.

NIKKI: To keep it real… for just a second…I mean, anger is part of it. But any of us that have gotten to positions of power have learned how to not scare people. What we have learned how to do is turn our rhythm into charisma that is magnetic and irresistible in a lot of respects. And I know that it’s spoken about, but it’s not acknowledged in the way that it deeply affects the psyche of black leadership.

We are expected to speak in a certain way, we’re expected to be charismatic, we’re expected to speak for entire groups of people.

MALIK: You know, for most of my adult life, I’ve done a lot of speaking to groups. And most of the time I’ve been speaking to exclusively African American audiences. And in speaking to African American audiences the passion is a plus. People want to be hyped up, you know. But as I got more involved in the food movement and began speaking to more mixed audiences, or predominately white audiences, that same passion, again, was interpreted as anger. And so I had to consciously learn how to…

D’ARTAGNAN: …code switch…

MALIK: …how to code switch, how to tone it down a little bit. I had to think about my thinking, and think about my speech, in order to not intimidate people. I wonder if part of this, though, is just a characteristic of American society…this looking for icons and wanting leaders to be perfect, and not really seeing leaders as human beings. I wonder if that’s a cultural characteristic.

D’ARTAGNAN: I’m now thinking about the expectations that we have, that are in some ways foisted upon us as black leaders. We’re expected to speak in a certain way; we’re expected to be charismatic; we’re expected to speak for entire groups of people. Like, Malik, when you leave Detroit, Malik Yakini is known for the food movement of Detroit.

MALIK: Yeah, that’s interesting.

D’ARTAGNAN: Nikki is known for the food movement of Oakland. D’Artagnan is somewhat known, right?…in the food movement of Southern California… In our role as leaders, in whatever movement we’re in (but specifically in the food movement) people attempt to play on these images of blackness in order to facilitate whatever their agendas may be. Sometimes they’re personal agendas; sometimes they’re more of a public agenda. But these expectations of blackness – that we be charismatic, that we be able to code switch, that we can’t speak with passion because it’s interpreted as anger, depending on the audience – those expectations can be destructive.

Some people in the movement, I’ve come to realize, rely on simple narratives in order to facilitate their own position. In Los Angeles, we have tons of fast food restaurants, but we also have grocery stores. The narrative is more complex. It’s not as simple as living in a food desert, or living in a food swamp, or some people not having access while others do. There are mobile markets that go out to our communities. Some people already had gardens before anyone even thought about funding garden builds, right? There is complexity that is not allowed in the construction of our identity as black people, but more specifically, as people who can be considered visible food justice leaders in the community.

Supporting these simple narratives and playing on images of blackness is counterproductive to the movement.

Supporting these simple narratives and playing on images of blackness is counterproductive to the movement. Partly because the simple narrative is the same old narrative – and it’s not true. It’s not true. These dominant ideological frameworks are constantly at play. These expectations of how we’re supposed to show up with one another, or the belief that black people must have moral leadership, or the belief that there’s always an appeal to white America for freedom, or for changing things. These frameworks keep us in a relationship of struggle and fight. And I’m not saying that these things may or may not be true – that we should not go out and mobilize our people through direct action organizing to demand power – because I do recognize that power concedes nothing without demand. However, what I am arguing, is that these constructions lock us into dichotomous relationships; they lock us into relationships that do not advance justice. These constructions essentially hold the status quo in place.

MALIK: Another thing is that as I listen to you talk about teaching people to be liberated, and that might not have been your exact words—what I’ve found in my own life is that the more I manifest [liberation] within myself, rather than try to teach people [liberation], or convince people of it, the more we fully express our humanness. We create a spiritual force—almost a spiritual generator, I think—that draws people to us, and has people wanting to be more like us, or to develop the qualities within themselves that they see in us, rather than us trying to convince them that they should do one thing or another. For me it’s not even a rational thing, you know, because you can give people information all day long and that doesn’t necessarily result in a change in behavior. So, at least in my own life, what I try to do is develop my own humanity to the fullest and to be an example, and I find that the more that I do that, there’s this almost invisible force that’s created that begins to call other people to move.

MALIK: Another thing is that as I listen to you talk about teaching people to be liberated, and that might not have been your exact words—what I’ve found in my own life is that the more I manifest [liberation] within myself, rather than try to teach people [liberation], or convince people of it, the more we fully express our humanness. We create a spiritual force—almost a spiritual generator, I think—that draws people to us, and has people wanting to be more like us, or to develop the qualities within themselves that they see in us, rather than us trying to convince them that they should do one thing or another. For me it’s not even a rational thing, you know, because you can give people information all day long and that doesn’t necessarily result in a change in behavior. So, at least in my own life, what I try to do is develop my own humanity to the fullest and to be an example, and I find that the more that I do that, there’s this almost invisible force that’s created that begins to call other people to move.

Click here to read and download the full publication at WhyHunger.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.