Column: Hear what small farmers are trying to tell us

By Rekha Basu, rbasu@dmreg.com

Retrieved from http://www.desmoinesregister.com

Trumpets sounded as luminaries’ named were called. One by one, to fanfare, the national and international guests entered the state Senate chambers and were seated among elected and nongovernmental officials, scientists and business leaders for the 2015 World Food Prize laureate ceremony.That was Thursday.

A night earlier, in a United Methodist church in Des Moines’ mid-city, guests pooled in through a back door. Some caught themselves swaying to the Andean-style flute and drums as they took their seats in church pews. Some were clad in blue jeans, some had beards and some wore sensible shoes. All were there to honor the plight of small-scale, direct producers of food.

It was a cosmic convergence of unlikely people, a scene you could spend the rest of your life trying to recreate. You had the Raging Grannies, white women in straw hats and fake flower garlands, singing classic American folk songs. You had the Southern black farmer, the white farming activist, the Afro-Caribbean matriarch and the Latino minister with dreadlocks. But when everyone joined at evening’s end to sing variations of “This land is my land,” and “Home on the Range,” you had a synergy.

Since the Food Sovereignty Prize was launched in Des Moines as a grassroots effort in 2009, its organizers have competed with the 29-year-old behemoth a few miles downtown to advocate a different approach to agriculture. The World Food Prize is awarded annually for individual contributions to increasing the quantity of food grown primarily through crop science and genetic modifications. The sovereignty award, on the other hand, promotes ending hunger by promoting agrarian reform, fighting climate change, and challenging consolidation of land in the hands of the wealthy few. Small farmers can’t necessarily afford the chemical fertilizers and other agricultural inputs associated with GMOs. They want varied crops, not monocultures, and seeds they can save and replant, which sellers of GMOs don’t permit.

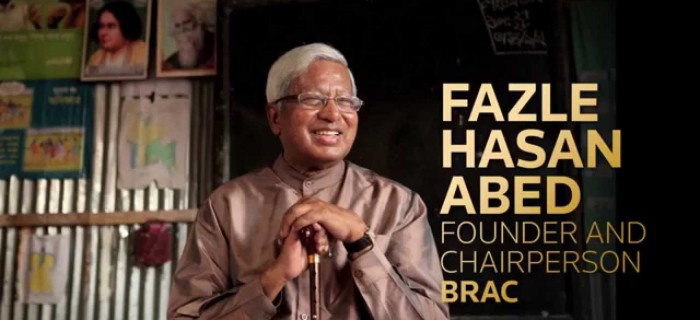

So it’s encouraging when occasionally the honorees of both organizations have similar objectives, as they seemed to this year. World Food Prize laureate Sir Fazle Hasan Abed of Bangladesh (he’s also been knighted by the British crown) made a stirring personal journey from Shell Oil executive to founder of the world’s largest nongovernmental development organization, the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC). Though part of Abed’s leadership has been in increasing yields by providing new seed varieties at fair prices, another part has been been increasing crop and livestock production through efficient farming techniques, stressing environmental sustainability and affordability — “ensuring that improved inputs and technologies are taken to the poor farmers.”

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

Sign up today!The Food Sovereignty Prizes went to the Federation of Southern Cooperatives and the Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras. The former begun during the civil rights movement in an effort to keep land in the hands of Southern African-American farmers. Black farm ownership in the United States has fallen from 14 percent to an alarming 1 percent in less than a century, according to executive director, Cornelius Blanding. The organization works to prevent corporate takeovers by promoting farming cooperatives and offering training and advocacy to farmers.

The Black Fraternal Organization of Honduras is devoted to protecting the land rights of Garifuna communities — descendants of indigenous South American Indians and black African slaves — along the Atlantic coastline. Frequently displaced by European settlers, the Garifuna have struggled to maintain their cultural and agricultural traditions and their right to produce their own food. But women in 43 of the matriarchal communities are struggling to defend their territories against a push toward American-style economies and lifestyles, said general coordinator, Miriam Miranda. “All of our resources are being destroyed in the name of this style of life,” she said in Spanish through an interpreter. “Our community has been displaced and destroyed to build this mega, industrialized agriculture.”

Iowa farmers faced similar problems and many gave up in the 1980s farm crisis. One who didn’t, Barb Kalbach, is a fourth-generation family farmer in Dexter, who told the gathering about her successful bid 13 years ago to keep a giant factory farm from going up by her house. She said the concentration of farm ownership into the hands of a few big corporations has been facilitated by influencing lawmakers “through commodity groups and a corporate advocacy group called the Farm Bureau.” And she referred to Iowa businessman Bruce Rastetter’s thwarted efforts at buying land and “displacing the indigenous and enriching the wealthy,” in Tanzania a few years ago.

A leader of the South African Right to Agrarian Reform Campaign decried exploitation by multinational and transnational corporations, and broken promises by anti-Apartheid leaders to return 30 percent of land to indigenous peoples; only 6 percent has been transferred back, said Petrus Brink.

It’s not that we don’t need food produced on a large scale to supply the supermarkets where we non-farmers shop. And the World Food Prize is doing better at recognizing genuinely humanitarian efforts by Abed and several others with a deep commitment to fighting hunger. But it’s time for the organization to drop its uncritical embrace of the Green Revolution approach to farming, or even the idea that all farmers need help. It should also show an understanding of what struggling farmers from Central America to Iowa are trying to tell us: That what they really need is non-polluted land, clean water, seed, and the means to resist their displacement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.