Fishing in the Bohol Sea

Walking up the road in the warm night, with the town sleeping around them, two men turn onto a dirt track between a few ramshackle houses towards the beach. Where the coconut palms meet the rocks and gravel, they pass young men who have wrapped themselves in thin colored cloth, and are sleeping on the ground, their heads invisible.

Fishing boats are drawn up onto the beach. The two men, a young teenager and an older man, walk over to the best-looking boat, painted red with indistinct words on the side. It’s a thin, shallow hull, with a small covered section in the middle over a small motor, and two white outriggers at the end of curving bamboo arms, one on each side. A big net is wrapped up under a cover in the middle of the boat.

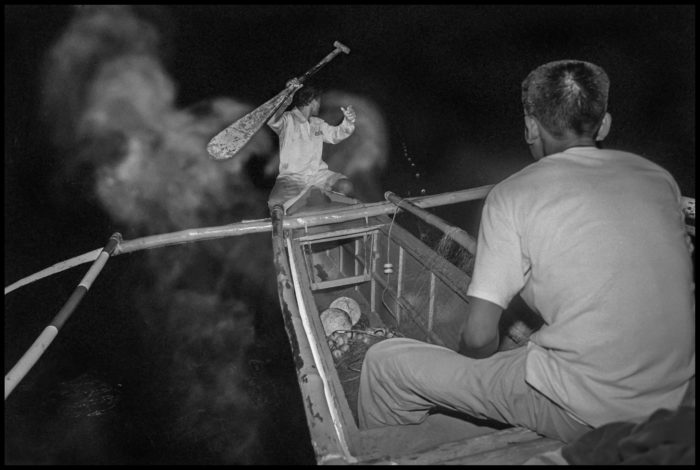

The sleeping men wake up. Together they begin pushing the boat on bamboo rollers down the beach. Lifting the outrigger arms, they slide the hull into the water, and finally the boat is floating in the small waves. It’s almost totally dark, but a crescent moon moves in and out of clouds crossing the sky.

The older man hoists a bag full of beer, and gingerly walks from the needle-nose prow down into the hold between the engine and the net, as the boat rocks gently beneath him. He is Ayon, the captain. Beboy, his helper, jumps on. Ayon starts the motor, and the boat pulls away from the beach.

Ayon loops a wire connected to the accelerator around his big toe. In one hand he holds a long pole connected to the rudder, while he guns the small engine with his foot. They set out into total darkness, the boat rising and falling with the waves. Bohol’s strange peaks are looming dark shapes on the horizon, above the tiny lights of the towns of Garcia Hernandez and Jagna.

They pass a couple of other boats on the way out. Ayon’s brother is a fisherman on one, its yellow light barely visible. Beboy shines a makeshift flashlight on the outrigger and into the dark water as they go, looking for fish. Finally, they set out their net, its long line of floats rising and falling with the waves. Ayon smokes a cigarette while he waits, drinking a beer. Beboy stands in the stern, watching for clouds and storms.

Photo by David Bacon

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

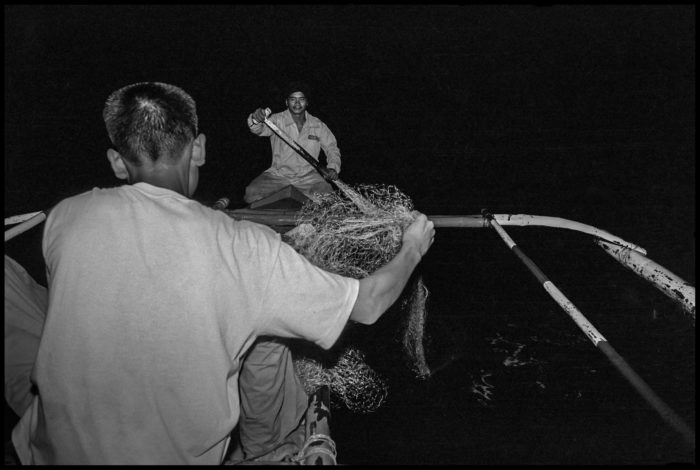

Sign up today!As dawn breaks and light slowly fills the sky, they pull the net in. Hand over hand, the web of filaments comes up the side of the boat, and as Beboy pulls Ayon looks for the fish. They are catching milkfish, or bangus. The muscles of these small, compact fish promise more meat than most fish their size, making them popular in the market. Bangsilog, bangus with egg over garlic rice, is a favorite breakfast in the Philippines.

The net in, and the fish in buckets, they turn the prow towards Bohol’s hills in the distance. In no hurry, the motor is barely audible above the sounds of waves and gulls as they head back to land. A small crowd greets them at the beach, performing the same boat-pulling exercise in reverse, dragging the hull up on bamboo rollers to its original resting place.

Meanwhile, women from the market stalls of Jagna look into the buckets, and argue with Ayon about the bangus’ size and price. They make their deal, and the morning’s catch disappears even before the boat stops moving. The last beers are passed around and drunk, and Ayon and Beboy walk slowly home.

Over a million people in the Philippines make a living from fishing, and 80% fish in small outrigger boats like Ayon’s. The country is made up of over 7000 islands, giving it the world’s largest discontinuous coastline, and making fishing an integral part of what it means to be Filipino. Fish are the number one source of protein in the diet of the people of the islands.

On the other side of the Bohol Sea is the big island of Camiguin. Here too, twenty years after Ayon and Beboy’s night of fishing, the boats go out every morning, coming back with their catch for the market. But here, as the women examine the catch, they see no bangus. They complain that the fish are small, hardly worth selling.

Mario Valladares, father of many of the fishermen on this beach, looks resigned as he mends his nets, as though he’s heard this many times before. His son Virgilio holds up a string of today’s catch, and explains that they can’t go any longer to the old fishing grounds of years past. The Philippine government has declared them an ecological preserve to protect the resource from overfishing. That leaves Camiguin’s small fishermen to find their catch in the areas that border it.

“The big fish just run for the preserve and hide. They know we can’t go there to get them,” Mario Valladares says. After the nets are mended, therefore, they carry their strings of fish with them as they head down the beach, planning to cook them for their own breakfast.

In the past, most Filipino fishermen were also farmers. As fish get scarcer, however, and sections of the sea are walled off, fishermen must travel further to find a good catch. When they don’t, as the Valladares family now frequently finds, they no longer have time to farm and the catch doesn’t pay for the gas in the boat.

The Valladares family’s predicament is the result of forces over which they have no control. The Philippine government ratified the Law of the Sea Treaty in 1978, which forced it to commercialize its fish resources in order to retain jurisdiction over its territorial waters. Commercialization meant attracting foreign investment for large fishing operations. Huge trawlers pulling purse seine nets scooped up huge quantities of marine life. Fish stocks plummeted, forcing the creation of no-fishing areas to try to allow the fish to recover.

Small fishermen were left behind – their old fishing grounds and fishing methods walled off by decree, and by the economics of a system in which they can not compete. Two decades ago Ayon and Beboy were able to make a living fishing on the coast of Bohol. The new reality for fishermen, though, is being experienced by the Valladares family on Camiguin.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.