Gates Agriculture Speech Highlights Sustainability but Falls Short

Bill Gates, Co-Chair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, delivered his first major address on agriculture last week on the occasion of the 2009 World Food Prize symposium in Des Moines, Iowa. The World Food Prize is awarded annually to pioneers in biotechnology, and Mr. Gates, whose foundation is at the forefront of launching a ‘new’ Green Revolution in Africa, gave the keynote presentation.

Just a few blocks away, at the annual Conference of the Community Food Security Coalition (CFSC), another award-the first annual Food Sovereignty Prize-was being presented to the international peasant movement Vía Campesina. With 148 member organizations in 69 countries, Vía Campesina has become a forceful and articulate voice in favor of rebuilding healthy agro-food systems, controlled by farmers and consumers, instead of corporations. The two parallel events were an apt symbol for two competing visions of our global food system: one engineered in laboratories and centered on global markets, and the other cultivated in the fields, and focused on communities.

Mr. Gates’s speech, however, highlighted some promising changes in the evolution of the Gates Foundation’s approach in rural Africa. For instance, the foundation’s decision to finally take sustainable agriculture seriously is potentially a boon to peasant producers, who already feed the continent, largely through organic methods:

That’s why our foundation works closely with local farmers’ groups. And that’s why we are one of the largest funders of sustainable approaches such as no-till farming, rainwater harvesting, drip irrigation, and biological nitrogen fixation.

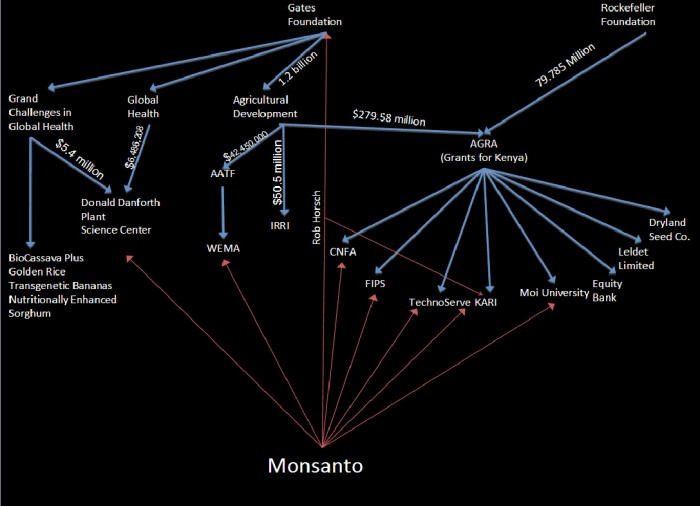

The Gates Foundation should be applauded for responding to the widespread criticism of its agro-industrial approach. Nevertheless, the continued support of and collaboration with agribusiness interests-which far outstrips funding for sustainable farming-continues to jeopardize farmer autonomy and self-sufficiency. Travis English, a researcher at the Seattle-based Community Alliance for Global Justice, was able to link the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA)-a Gates Foundation led initiative-to at least $100 million in grants linked to the GM seed giant Monsanto. In Kenya, where a large number of AGRA grants are concentrated, 79% involve biotechnology in one way or another, found English (see chart below). Thus, while we admire the Gates Foundation’s recognition of the benefits of sustainable agriculture, the foundation clearly remains heavily implicated in the broader push to re-structure rural Africa along more “business-friendly” lines, the so-called Green Revolution. The overarching objective of this movement is first and foremost the commercialization of African agriculture. Whether this is portrayed-either cynically or altruistically-as a way to help farmers and feed the hungry, profit (often rendered as “growth”) is the real endgame.

To his credit, Gates acknowledged the environmental and social damage wrought by the first Green Revolution of the 1950s and 1960s:

Many environmental voices have rightly highlighted the excesses of the original Green Revolution. They warn against the dangers of too much irrigation or fertilizer. They caution against a consolidation of farms that could crowd out small-holder farmers. These are important points, and they underscore a crucial fact: the next Green Revolution has to be greener than the first.

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

Sign up today!It is unclear how the new Green Revolution will be “greener” however, with a strategy based on promoting the use of GM seeds-which go hand-in-hand with chemical inputs.Joe DeVries, Director of AGRA’s Program for Africa’s Seed Systems, makes this clear: “New crop varieties are the engine of growth for a Green Revolution in Africa. Without the appropriate use of fertilizer and the adoption of improved seeds, farmers will not be able to produce the yields needed to transform smallholder agriculture.” Gates himself reproduces not only the assumption that peasants are under-productive farmers, but that they are poor environmental stewards as well:

When productivity is too low, people start farming on grazing land, cutting down forests, using any new acreage they can to grow food. When productivity is high, people can farm on less land.

It is generally recognized that although small farmers may become agents of deforestation, their behavior is guided by a complex web of structural causes such as displacement by armed conflict, mega development projects or brazen “land-grabbing”. And although simple “low productivity” may in some cases motivate environmentally destructive practices, it is less likely to be caused by a lack of “modern” technologies than by a lack of land.

The fact is, small farmers are already more productive on less land-because they have no choice but to cultivate every last square inch. It is the large landowners who often maintain acres upon acres of idle or underutilized land. Moreover, peasant farming systems, which are usually more diversified, have been shown to produce greater yields per acre than monocultures (See Rosset, Peter. “On the Benefits of Small Farms” Food First Backgrounder, Winter 1999). In other words, small farmers are plenty productive without GM seeds and chemical fertilizers, thank you very much. What they need is more and better land-and support for the production systems they already have: those that have sustained them through decades of neglect; the dynamic knowledge systems and constantly evolving agroecological methods that have rarely, if ever, benefited from any kind of subsidy.

Gates also neglects to mention the proven health risks associated with the consumption of GM crops. A recent book by Jeffrey Smith compiles the results of 65 peer-reviewed scientific studies documenting these risks. Lab animals tested with GM foods in these studies showed a wide range of impairments including stunted growth, impaired immune systems, bleeding stomachs, abnormal and potentially precancerous cell growth, impaired blood cell development, inflamed kidneys, less developed brains, increased death rates and higher offspring mortality.

Nonetheless, Gates insists that the real threat to small farmers is the “ideological wedge” between “a technological approach that increases productivity” on the one hand and “an environmental approach that promotes sustainability” on the other:

Productivity or sustainability – they say you have to choose. It’s a false choice, and it’s dangerous for the field. It blocks important advances. It breeds hostility among people who need to work together. And it makes it hard to launch a comprehensive program to help poor farmers.

In fact, there is no ideological wedge between productivity and sustainability. Rather, there is a political difference between conflicting development models. This difference need not be viewed as “hostile” or disabling, but as an expression of healthy democratic debate. Food First agrees wholeheartedly with Mr. Gates that rural development “must be guided by small-holder farmers, adapted to local circumstances, and sustainable for the economy and the environment.” We hope this enlightened position signals the Gates Foundation’s willingness to engage more actively in a transparent and inclusive debate about what exactly that means, and how best to carry it out.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.