Banana War in the Philippines

Food First Backgrounder, Summer 1998, Vol. 5, No. 2

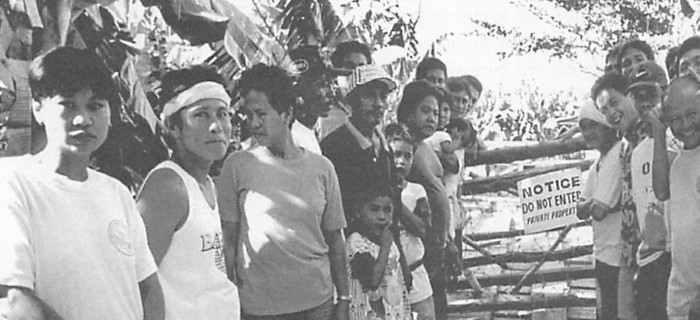

For the past several months, the banana groves on four Philippine plantations have been uncharacteristically silent. In place of the normal cacophony of harvesters cutting huge banana bunches, men and women sit quietly all day in dusty tents beside the plantation roads. On December 4, 1997, almost 2,000 farm workers stopped cutting bananas for the Dole Corporation. Thousands of harvesters on other Dole plantations are following the work stoppage closely. Another 2,500 have served notice they intend to join the strike. This dispute, which could paralyze most of Dole’s Philippine banana operations, highlights the possible consequences of economic liberalization in the wake of the economic meltdown in southeast Asia.

Out-Sourcing the Global Banana

There is a clear downside to the growing tendency of global food companies to “out-source,” that is, to transfer ownership of their plantations to former workers. Those workers then assume all the risks of farming, including low prices, drought, and pest and crop disease epidemics. They often have to buy the necessary chemical inputs, seeds and machinery in U.S. dollars, whose prices rise during currency devaluations while those for fruit and vegetables plummet. Meanwhile, the original company retains exclusive marketing rights and the ability to arbitrarily fix prices. As the company buys the same product in many different countries, it can effectively play farmers off against each other. Dole, with operations in 80 countries, is the world’s largest grower of fresh fruit and vegetables, and the largest producer of bananas. The Filipino workers have been striking over the low price Dole pays for each box of bananas they harvest.

Recently two of the struck plantations reached an agreement with the company on an increase to $2.60 per box. More important, Dole agreed to pay in dollars to offset the devastating effects of the peso’s current devaluation. However Dole has refused to apply the same terms to the other two plantations being struck. Until two years ago, all 2000 strikers were direct, salaried employees of Dole’s subsidiaries Stanfilco, Checkered Farms and Diamond Farms. Their wage scale started at 146 pesos a day, and the company paid for medical care, pensions, vacations and sick leave. They were members of the National Federation of Labor (NFL), one of the Philippines’ most militant unions, and were covered by a collective bargaining agreement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.