Philippine Banana Farmers: Their Cooperatives and Struggle for Land Reform and Sustainable Agriculture

To download a PDF version of this Issue Brief, click here.

Thirty years ago many banana workers in the Philippines made a radical change in their work and lives. They transformed the militant unions they had organized to wrest a decent living from the multinational corporations that control much of the world’s food production. Instead of working for wages, they used the country’s land reform law to become the owners of the plantations where they had labored for generations.

It was not an easy process. They had to fight for market access and fair prices against the same companies that had been their employers. But they developed a unique organization to help them, that provided knowledge and resources for forming cooperatives. Twenty years ago FARMCOOP and these worker/grower cooperatives defeated the largest of the companies, Dole Fruit Company (in the Philippines called Stanfilco). As a result, today the standard of living for coop members has gone up, and workers have more control over how and what they produce.

FARMCOOP became the source of everything from financial planning and marketing skills to organic farming resources and political organizing strategy. FARMCOOP then developed an alliance with one of Mindanao’s indigenous communities, helping it start its own coops that combine the use of local traditions with organic and environmentally sustainable agriculture.

The experience of both sets of cooperatives points to an alternative to the poverty that grips rural people in the islands. The Philippines is an economically poor country—the source of migrant workers who travel the world to work because they can’t make a living at home. More of the world’s sailors are Filipinos, for instance, than any other nationality, recruited in shapeups each morning outside Rizal Park in Manila.

According to the FAO, “Only the remittances of migrant workers to their families have enabled the latter to survive crippling poverty brought about by stagnant agricultural productivity, stiff competition from cheaper food imports, and periodic droughts and floods that devastate crops and livelihoods.”

The struggle of FARMCOOP and the cooperatives created an alternative to forced displacement and migration, changing the lives of their own members, and providing valuable experience for workers and farmers elsewhere in the Philippines, and in other countries as well.

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

Sign up today!The Genesis of the Agrarian Reform Law

One hundred and eight million Filipinos today inhabit a country of 115,000 square miles in over 7000 islands. Over half still live in rural areas—two-thirds on just two islands, Luzon and Mindanao. In 1991 there were over 11 million landless farming families, about 40% of the total agricultural population and a number that had more than doubled in 20 years. Landless families today still number in the millions.

It’s no accident that the 300-year history of the Philippines as a colony of Spain, and its half-century as a colony of the U.S., were marked by repeated uprisings of farmers. And while the Philippines won independence in 1946, the struggle over land continued to be the defining question in the country’s politics. Since the start of US colonization, different Philippine governmental administrations all proposed some degree of land reform, often simply to head off revolts like that of the Sakdalistas in the 1930s, or the Huks in the Cold War years after independence.

According to a report by E.A. Guardian for the Food and Agriculture Organization, “When peasant uprisings broke out in the 1930s, during the period of the Commonwealth, President Quezon introduced a massive resettlement program. This program was pursued by President Magsaysay after the Pacific War to break the backbone of the Huk Rebellion. The government opened up vast uncultivated and unpopulated areas for homesteading, especially on Mindanao Island. This created another problem: it marginalized the indigenous population, as some of the resettlement areas intruded into ancestral domains. This is one of the roots of the current conflict in Mindanao.”

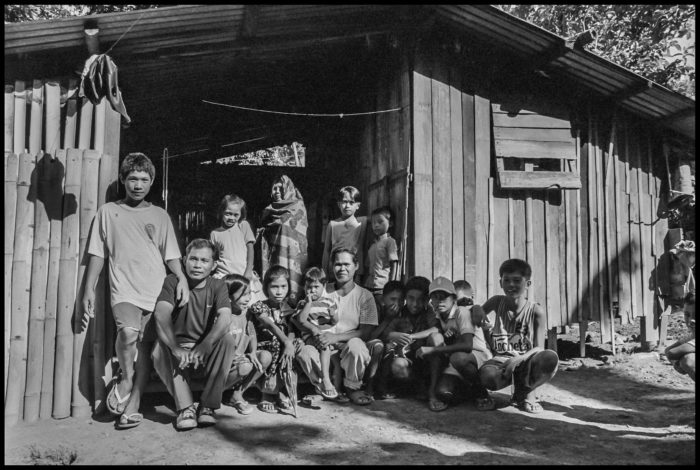

The home of Felix Bacalso, a banana coop member and striker (1974). Photo copyright © 2020 by David Bacon.

Large corporations were often the beneficiaries. While a U.S. colony, the Philippines welcomed investment by multinational corporations. Former government lands were sold off to create plantations—part of the development of an export-oriented economy. On Mindanao Castle and Cook, and the family of James and Sanford Dole, who earlier introduced the plantation system in Hawaii, set up the first plantations for bananas and pineapples. US and European rubber corporations set up latex plantations in Basilan. Agricultural production for export has been a pillar of Philippine economic development policy ever since.

To bring the bananas to market, Philippine and U.S. investors established the Dole subsidiary Standard Philippine Fruits Company, or Stanfilco. Stanfilco soon produced bananas on four Davao farms, including 700-hectare Diamond Farms, 689-hectare Checkered Farms and 464-hectare Golden Farms, in partnership with Filipino investors in the House of Investments. By 2007 the Philippines had become the world’s third-largest producer of Cavendish bananas, after Ecuador and Costa Rica, much of them coming from the Davao plantations.

Local residents and people migrating from elsewhere in the Philippines became the workforce, and in the 1960s they organized unions. The Zamboanga Federation of Labor and the Mindanao Federation of Labor started on the plantations. They eventually became the nucleus of a nationwide union bringing together workers and leftwing political activists from many industries—the National Federation of Labor. Even more conservative unions, like the Associated Labor Union, negotiated for workers in some of Mindanao’s corporate agricultural enterprises.

Martial law, declared by Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos in 1972, made labor organizing dangerous, and farmworker leaders and political activists often had to go underground. Nevertheless, despite violence and repression, strikes and labor conflicts were common. Consequently, the expectations of Filipinos after the fall of the Marcos dictatorship were very high that the People Power Revolution would make real labor and land reform possible. Armed struggles by both the New Peoples’ Army and the Moro National Liberation Front in Mindanao showed the likely consequences of keeping in place the existing land monopolies by wealthy families and large corporations.

On January 22, 1987, as a new constitution was being written, and with the government of President Corazon Aquino only recently in power, ten thousand farmers, farmworkers and activists marched towards the presidential residence in Manila, the Malacañang Palace. On the Mendiola Bridge soldiers opened fire. Twelve people were killed and 19 injured. Several of Aquino’s cabinet members resigned in the face of the “Mendiola Massacre” and six months later she proclaimed Executive Order 229, a first step in land reform. Congress followed the next year by passing Republic Act No. 6657, the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP).

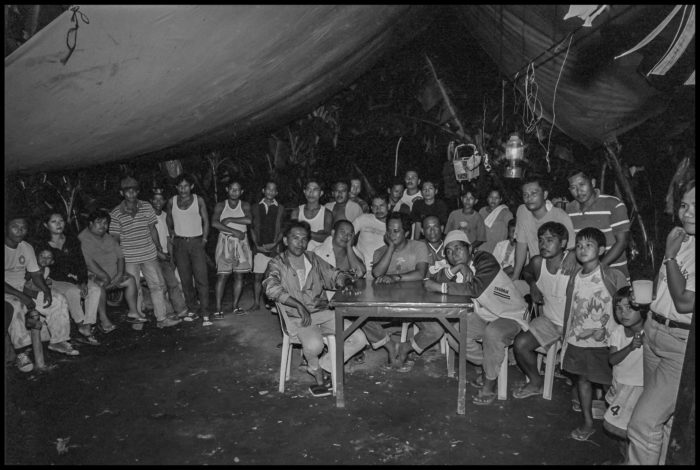

The coop strikers – thrown off the plantation and picketing on the highway (1974). Photo copyright © 2020 by David Bacon.

The law was a complex compromise, and in its first years leftwing activists even tried to implement their own alternatives to it. The Act did, however, set up a process in which workers could petition to become owners of the land on which they labored. The government set aside a fund for compensating owners, who were not allowed to retain more than five hectares. There were holes in the law. One allowed corporate owners to transfer stock ownership to workers instead of land, which led to one of the Philippines’ longest and most bitter land disputes at Hacienda Luisita, owned by Aquino’s own family. Another allowed land transferred to workers to be sold after ten years.

According to one study, after 12 years the Department of Agrarian Reform had redistributed 5.33 million hectares of land, 53.4 percent of the Philippines’ total farmland, to 3.1 million rural poor households. The law was set to expire in 1998, but was extended for another ten years, and given a new appropriation, by the administration of President Fidel Ramos. It was extended again to 2014 by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, after which only cases still pending would continue.

The New Coops Go on Strike

Before the agrarian reform passed in 1988, workers on the Davao banana plantations were wage workers, members of the National Federation of Labor (NFL). Hard-fought collective bargaining agreements protected their wages and benefits. Nevertheless, according to FARMCOOP, “abject poverty characterized their quality of life. Thus, CARP in 1988 was a welcome government instrument to improve their lot.”

At the time the law passed, Koronado Apuzen was an attorney for the NFL, responsible for the union’s activities on the Mindanao plantations. “ When they were discussing agrarian reform at first we were still more concerned with trade unionism,” he recalls. “When the law was debated the NFL didn’t push actively for it. But after it was passed, we decided to look at how it would be implemented. The NFL then was the biggest labor federation in the agricultural sector. So in one of our conventions our theme was ‘Unionism beyond collective bargaining.’ We asked ourselves, would a trade union still be possible when the workers became owners of the land?”

For the union to see its members as potential landowners and growers themselves, rather than wage workers in a union, was a big change in perspective. But the union’s radical politics helped it make the shift. Apuzen explains: “Distribution of the land to the farmworkers was a fulfillment of what we had been teaching them as a political union – that in order for workers to win social and economic justice the forces of production must be placed in their hands. In agriculture the land is the basic force of production. So if placed in the hands of workers, we have attained that goal … some kind of socialist society or setup, in the context of agrarian reform.” Jesus Relabo, a founder of the coop on the DABCO plantation, says simply, “Owning the land is forever. It’s something you can give to your children.”

To help workers implement the law, in the early 1990s the union organized associations that applied for land ownership. After the associations were given the certificate of land ownership, the union helped to transform them into cooperatives, in which the land title was held by all the beneficiaries. Workers also received severance pay from the former landowners. Apuzen and the union then set up an independent organization, FARMCOOP, to continue to help the cooperatives, which made up its governing board. It got funding from Bread for the World, a German international foundation.

The union and the workers had no experience in negotiating contracts with Dole/Stanfilco, however. “In FARMCOOP we didn’t know what contract to propose,” Apuzen remembers. “We didn’t know the intricacies of the banana business, or what kind of arrangement would be best for the coops. That gave the company the ability to impose the kind of contract it wanted.” The Department of Agrarian Reform allowed Stanfilco to retain ownership of the roads on the plantations, the cableways needed to bring the bunches into the packing shed, and the packing plants themselves. And Dole controlled the market in Japan, South Korea and the countries to which the bananas were exported, and the ships and ports needed to get the bananas there. That gave the company enormous leverage in negotiating the first agreements. When the coop members suggested a clause in their agreement that would have allowed them to sell bananas to other companies, Dole said it would refuse to let them use that infrastructure.

Coop members today still refer to them as the “onerous contracts.” The company managed the plantation operations, and provided the fertilizers and pesticides necessary for its production system. It charged for the use of its assets, transportation to the port, “wharf fees,” and other expenses. The coops were responsible for paying the cost as calculated by Stanfilco, which then turned over the net proceeds. For the coops, the result was economic disaster. Their wages dropped from 140 pesos to 92 pesos a day and they lost all the benefits earned through collective bargaining. Worse, they incurred heavy losses and debts because the price of their bananas was below production cost. The Diamond Farms coop lost 30 million pesos the first year, and Checkered Farms 11 million. And the duration of the contracts was at least ten years.

The agreements proved so controversial they were initially rejected by the workers. Nevertheless, in the end, they were adopted. Workers charge that Dole took advantage of their lack of knowledge during negotiations. “The company promised we would make big profits if we produced over 3000 boxes of bananas a day, but even after meeting that goal, our coops lost money,” explains Eleuteria Chacon, chairperson of the coop at Checkered Farms. “We didn’t really understand how to compute our costs, and the company said they wouldn’t negotiate with us if we brought in experts from our union.” Dole also withheld the workers’ legally-mandated severance pay until they signed the agreement, she says.

One Diamond Farms worker, Felix Bacalso, had to pull all but two of his 10 children out of public school, no longer able to afford the small tuition and the cost of uniforms, food and transportation. “I’m worried I’ll have to send them to work if the company doesn’t pay more,” he said at the time. “As it is, some of my kids have had to go live with relatives.”

After seeing the result, FARMCOOP and Apuzen realized that the only solution was to force the abrogation of the “onerous” contracts, and the negotiation of new ones. They met with coop members, and convinced them to take the same kind of action they knew from their previous experience as union members – to stop producing bananas, essentially to strike.

“When the time came, and the coops complained of heavy indebtedness, and becoming poorer because of the contracts, we had to decide,” Apuzen says. “And they decided in favor of organizing, and strengthening each coop and their unity. While we were doing that, we wrote Dole asking the company to renegotiate the contract. Dole refused, so we had no choice but to prepare for a concerted action. The coops organized the Philippine Alliance of Banana Growers.”

From December 1997 to February 1998 almost 2000 coop members in four coops refused to pick bananas—Diamond Farms (DARBMUPCO), Checkered Farms (CFARBEMPCO), the Davao Abaca Plantation Company (DARBCO) and Stanfilco Employees Agrarian Reform Beneficiaries Multipurpose Cooperative (SEARBEMPCO).

The growing confrontation escalated into violence. On December 4, according to Antonio Edillon, a Diamond Farms banana harvester, over 500 armed men attacked 100 people on the picket line. “We sat down at the edge of the banana grove, beside the main road, and locked arms with each other. I was hit by an iron bar, and I saw others hit and kicked as well. The soldiers pointed their Armalite rifles at us, and told us they’d shoot.” When Roberto Sabanal rushed across the plantation to help, he was shot in the back and wounded.

The attackers were members of the 432nd Infantry Battalion of the Philippine Armed Forces, along with local police and guards from Timog Agricultural Corp., a division of Dole Asia, Inc. They dragged the picketers onto busses and took them to Carmen, a nearby town. The picket line was broken, and armed guards entered the plantation. Strikers were expelled, and afterwards ate and slept under tarps at the edge of the highway. One guard in camouflage fatigues, his head wrapped in a bandanna and holding an AR-16, said he worked for Stanfilco, a division of Dole Philippines, Inc.

Jean Lacamento, now a board member of the DARBMUPCO cooperative, remembers that “for three months we lived under the banana trees. We owed 3.8 million pesos to the company, and we knew we’d never get out of debt if we didn’t win. We couldn’t feed our families or send our kids to the hospital when they were sick.” According to Joel Adran, now the coop manager, “the company sent in armed men during our negotiations. They tried to bribe our coop officers. When the police came after us, we hid in the FARMCOOP office for two weeks.”

Finally, Apuzen sent an appeal to the International Union of Foodworkers, an international labor federation based in Geneva. In response, Ron Oswald, IUF president, wrote to Dole and threatened to organize a global boycott of Dole fruit through its affiliated unions if the dispute in Davao wasn’t settled. Dole gave in, and the onerous contracts were abrogated.

FARMCOOP helped the cooperatives negotiate new agreements from February to November. The four struck plantations negotiated a flat rate of $2.60 per 13 kilo box of Class A bananas. Dole agreed to pay in dollars to offset the devastating effects of the peso’s devaluation. Most important, Dole/Stanfilco became simply the buyer of the bananas at the contract price, under a ten-year contract, while the coops managed the plantations themselves. The coops paid Dole 7¢/box for transport from packing shed to the wharf, 8¢ for stevedoring, and 8¢ for rental for cableways, the irrigation system and the packing plant. After deducting expenses like Sigatoka pest management, drainage, bridge repairs and road maintenance, farmers got about $2 per box. Of that they had to hire other workers for maintenance and packing, and in the groves themselves. The coop members, referred to as Agrarian Reform Beneficiaries (ARBs) also received dividends from the coop itself.

Rising Income in the Coops

The new agreements brought immediate improvements to the cooperatives’ families. FARMCOOP estimated that their income rose 126% in the first two years. The coops were able to pay amortization on their land, healthcare and social security premiums to the government, and the old debts to Stanfilco. Banks even offered loans, which the coops generally refused, since they were able to pay for their own inputs from the higher price they were receiving.

The movement to abrogate onerous contracts spread. Six other coops of 400 small farmers went on strike against Stanfilco for three months to win an agreement negotiated with the help of FARMCOOP. Former President Joseph Estrada intervened and Stanfilco finally signed. The coops set up a marketing arm, the Federation of ARB Banana-based Cooperatives of Davao (FEDCO) and by 2002 it had 16 member coops with 3,588 farmers owning 4,670 hectares of bananas. Nine were ARB coops and seven were small contract grower coops. FEDCO marketed Class B bananas, while the Class A bananas were exported under direct marketing contracts with the individual coops.

“All the agrarian reform coops started with a collective approach,” Apuzen says, “because we inherited the structure that came from Dole. The coop became essentially the employer of the workers. After we abrogated the first onerous contracts, this structure worked well for three or four years. But production began to decline. That’s when some of the coops changed their structure to the Individual Farming System (IFS). In that system, all the planted areas are divided equally among the coop members. But instead of receiving wages and a dividend based on the coop’s income, the income of each farmer depends on the productivity of their individual land.”

In 2001 the DARBCO coop, using a modified system in which producers were grouped together in groups of ten families, was the top producer, with 3736 boxes of bananas per hectare. The next year the DARBCO coop using the IFS produced 3836 boxes per hectare. And in 2003 CFARBEMPCO, also using the IFS, produced 4854 boxes per hectare. That meant workers had a higher income, which gave them a better life. On the DARBMUPCO plantation, income for its 715 coop members rose from 3500 pesos/month after the onerous contract was abrogated to 20,000 pesos/month in 2004.

Income went up again in 2007, when the 10-year agreements with Dole expired. The DARBCO coop, the first to negotiate, demanded a higher price in a new contract. The company refused. After bargaining with Dole failed FARMCOOP helped to negotiate contracts with another buyer, Unifrutti Tropical Philippines. The contract price was $2.75 per box, but Unifrutti bought bananas at prices higher than those stated in the contractswhen foreign exchange rates favored the coops, as much as $3.30. Even more important, it eliminated the old charges for hauling and wharf documentation. By 2015 Unifrutti was paying $4.05, and that year raised it to $4.50, to eliminate “pole-vaulting”—a practice in which growers sell bananas to other buyers under the table who are willing to beat the contract price.

“Our struggle began with the People Power strike,” remembers Esteban Cequiña at DARBMUPCO. “Our lives now have increased by 500% compared to what we had before. So the bananas have brought a lot of good to our children. Before it was hard to feed them or keep them in school. We had no hospital or medicine and when they got sick we had to go to the owners to beg for money to pay for it. I remember that I cried in front of the accountant for the House of Investments.”

Coop members all talk especially about the changes in the lives of their children. “We’ve been able to educate them to become professionals,” says Ronald Valencia, chairman of the DARBCO-IFS coop. “Before it was very hard to keep them in school. We used to say that with Dole we had Acute Income Deficiency Syndrome.”

“I sent my daughter to the Ateneo school in Davao,” adds Demetrio Patiño. “We had to struggle to make ends meet before. Now I own my own house, I have savings, and I have a car. I used to get around on a bicycle. There was a lot of pressure from the bosses in the old days. Now I’m the boss. We were ordinary workers, and now we manage a multi-million dollar business.”

The standard of living rose even higher at Checkered Farms, where the CFARBEMPCO coop organized a credit union and a coop store on the plantation, and started raising pigs. It now provides a burial service and loans for education and health care. Like DARBCO it also bought more land to expand production. It provides food and support to local schools, and grants for community projects. “Our life changed,” explains Carmela Pedregosa, the coop’s manager, “from being plantation workers to being owners of the land. I’ve been able to go abroad to Hanoi, China and Japan as part of my job.”

Family relationships changed as well. Women are much more active in all the coops, and in CFARBEMPCO they hold most of the leadership positions. “This was always true here,” according to Eleuteria Chacon, a leader of the 1998 strike. “But our men are good, gentle, kind and morally upright. They listen, and if women suggest plans men consider them. They respect women and the women here have no vices.”

Having educated children has created problems, however, since their expectations are different from their parents. The cooperative members are getting old, and if their now-adult children aren’t interested in farming, that creates problems for the future of the coop. The coops do create positions for office workers, accountants and technical support staff, and the children of coop members are encouraged to fill those jobs.

“I try to explain to my children that the farm, that bananas are the source of the money that sent them to school,” says Marigina Famador at DARBCO. “I hope they appreciate that. Banana farming is really important in the lives of our families, and it’s an important thing to do with our children. If they don’t understand its importance, they will think their education or advantages are a gift from the government. Even if they don’t farm themselves, they can contribute in other ways. I have a daughter who’s a CPA and gives time after work using her skills. And I have another child who didn’t want to go to school, and instead wanted to work to help his father. He says he’s going to work here and someday be the one to take over the farm.”

At Checkered Farms the coop made a commitment to pay office and support workers the normal salary that they might receive in a similar position in Davao City or Manila. It’s still not the income a daughter or son might get if they emigrate to the U.S. or another richer country, “but I hope that 20 years from now our children will be running the coop,” Pedregosa says. In the meantime, if a member decides to sell, the coop will discourage them. “So far that’s only happened twice, and both times people changed their minds. We offer them a loan if they’re in need. And if we have to, the coop can buy the land to makes sure it stays in the coop.”

As they get older, coop members also rely more on hiring people to do the work in the banana groves. Many of these hired workers are family members, who get a minimum wage set by the coop, as well as vacations and payments for housing, social security and the country’s health insurance, PhilHealth. On the Checkered Farms plantation there are about 80 hired workers. “Perhaps they should become coop members eventually,” Pedregosa says, “but we haven’t really talked about that yet.”

Eleuteria 20 years later as chairwoman of the Checkered Farms coop. Photo copyright © 2020 by David Bacon.

In 2010 FARMCOOP participated in developing a voluntary code on decent work, that includes promoting social partnership, job creation and employment security, equal employment opportunities for men and women, youth, seniors, indigenous and differently-abled persons, and systems to ensure food safety, environmental and worker protection and animal welfare. The code was signed by a large number of Mindanao unions and employers.

Political Organizing and Continued Corruption

FARMCOOP and the cooperatives all belong to the National Confederation of Cooperatives, composed of 1,200 cooperative affiliates with assets of 26 billion pesos and 1.2 million estimated members. In 1998 the Philippines introduced a party-list system of representation, and in 2004 the coop federation won a seat in the Philippine Congress after it won 270,950 votes, or 2.1% of the votes cast. An organization has to pass a 2% threshold to gain a party list seat. In 2007 it got 360,155 votes, or 2.46%. Its elected Congressman was Guillermo Cua, who died in 2008.

In 2010 the COOP-NATCCO Party List won two seats with 930,319 votes – sixth place among party list rankings, electing Jose R. Ping-ay and Cresente C. Paez. Ping-ay chairs the Congress’ Committee on Cooperatives Development and Paez is vice-chair. Their agenda was the reorganization of the government’s Cooperative Development Authority to make it more responsive to the coops. Paez explained that “a true coop doesn’t start with financial capital, but with social capital. The government needs to help the coop sector as part of a wider poverty reduction strategy.”

In 2012 the Mindanao coops decided to form their own party list, the 1 KOOP MINDANAO PARTY LIST. FARMCOOP published a 7-point program by Koronado Apuzen, which called on the coops to become the voice of the marginalized, win 1.2 million votes, and get coop leaders to participate in local elections. In Davao the party list made a commitment to build a farm-to-market road to help get bananas to the wharf, and facilitate the mobility of people.

On a local level, Ramsi Adran was elected a Davao municipal councilor. He comes from a DARBMUPCO coop family, and worked for FARMCOOP as a technical advisor. “The 37 coops in this region supported my election in 2016,” he explains. “My goal is to get the Department of Agriculture to give priority to the coops. Before this the coops weren’t visible on a political level.

In ten years the government only appropriated 50,000 pesos to help them. We’ve increased that to 450,000 this past year for training and leadership development alone.” Coop members gave money, and went door to door to help Adran get elected, and he’s been joined by other coop-supported candidates on a provincial level.

Despite these political advances, not all coops have had positive experiences. When the Davao plantation coops were being organized in the mid-1990s, the workers at Hijo Plantation Inc., which belonged to the elite Tuazon and Lim families, formed the Association of Workers at the Hijo Plantation. As they were in the process of joining the National Federation of Labor the owners split their lands in order to defeat their efforts. When the agrarian reform law was implemented, two groups formed the HEARBCO-1 and HEARBCO-2 cooperatives, winding up with the same kind of onerous contracts with no expiration dates. “We knew it was bad, but they told us we couldn’t have FARMCOOP or attorney Apuzen with us, and that we would not get severance pay if we didn’t agree,” recalls HEARBCO-2’s chairperson Alberto Verula.

They also wound up chained to a price below their production costs, and soon found themselves millions of pesos in debt to the old owners. Even Dole seemed preferable, so they negotiated a secret agreement to sell their bananas to Dole under the new terms the other coops had negotiated. Workers put up their own packing shed, but when they tried to begin delivering their bananas the old owners told them they couldn’t even cross the roads they owned. At the edge of one road company managers ordered their guards to shoot, and two coop members were killed.

For two decades people in the HEARBCO-1 coop wound up chained to the old owners, and then to their successors, the Lapanday Company, which belongs to the wealthy Lorenzo family. Legal cases went against them. In 2016 the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization found that contracts like the one at HEARBCO-1 cheat farmers through unlawful labor practices, no social protections and low lease rates. Under the Lapanday contract the company set the buying price at $2.10 per box for bananas exported to Japan, much lower than normal. It allowed the company take over management of the coop if it failed to follow “prescribed cultural practices.” The coop now owes 720 million pesos, and coop members are desperately looking for someone else to buy it just to settle the debt.

A further crooked contract gave control of HEARBCO-2’s land to the Tuazon family, which promised workers a million pesos per hectare to ratify it. The family announced plans to incorporate 294 hectares of coop land into an international industrial park in the city of Tagum, “We’re too tired to continue fighting or even appeal the case,” Verula says. “What the company and TAGUM authorities are planning is not legal, but when your family is starving, people will do what the company wants.” In a recent full-page ad in a national daily, with a congratulatory message from President Duterte, the development is called by Tagum’s mayor a “City within a City.”

The largest banana plantation in the Philippines is actually a prison farm in Panabo, outside of Davao City. The Tagum Agricultural Development Company, or TADECO, started by Antonio Floirendo in 1950, negotiated a joint venture with the Bureau of Corrections to set up a plantation on 5,308 hectares of a vast prison farm, the Davao Penal Colony. Today TADECO uses the labor of 764 of the prison’s 6,115 inmates, justifying it as part of their rehabilitation towards eventual social reintegration. TADECO then sells its bananas to Del Monte Philippines, which exports them throughout Asia and the Middle East.

Antonio Floirendo Sr. was such a close associate of President Ferdinand Marcos that some news reports speculate that Marcos was actually a secret partner in TADECO. The day before Marcos fell in 1986, Floirendo fled the Philippines. A year later he was forced to return to the government over $1.5 million in illegally-accumulated assets, including the mansion in Honolulu where Marcos lived in exile. Floirendo’s son, Antonio “Tonyboy” Floirendo Jr., became congressman for the 2nd District of Davao Del Norte, and his grandson, Antonio Lagdameo Jr. served in the same office.

Environmental Threats and Going Organic

Despite the economic gains in many of the coops, and the threats to the land and livelihood of others, one existential threat hangs over all of them. The spread of two plant diseases is already affecting thousands of hectares, and if the history of a half-century ago repeats itself, banana cultivation as the coops practice it may no longer be sustainable or possible. The threat comes from Fusarium wilt (Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense), known technically as “Tropical Race 4,” and black sigatoka. Both are fungus infestations. Fusarium wilt attacks the roots of the plant, and sigatoka its leaves.

The leaves of plants infected with Fusarium discolor and distort, and the plant eventually collapses and dies. Fusarium wilt spreads on a banana plantation because of the way the plants are cultivated. The banana itself does not contain seeds, and the male flower produces no pollen, making sexual reproduction impossible. Instead, the tree produces one large bunch of fruit, and after it is harvested the plant itself is cut down by the harvester. At the base of the tree a new sucker appears and produces a new tree. New trees are propagated by planting suckers from old ones. However, if suckers are used from old trees that were infected with Fusarium, then most likely the new tree will be diseased as well, even if the sucker shows no evidence of disease. The plants are genetically nearly identical, which makes them especially vulnerable. The fungus also produces spores that can last in the soil for decades.

Until the 1960s the variety of banana grown commercially worldwide was called Gros Michel. Fusarium wilt then began to appear first on plantations in Panama, giving it the nickname of “the Panama disease.” It soon spread globally, leading to devastation especially in Central America. There growers switched to a different variety, the Cavendish, which seemed to be immune to the disease, and which then became the variety cultivated everywhere. But a new variety of Fusarium called Tropical Race 4 appeared in southeast Asia in the 1990s. It attacked the Cavendish banana, and soon began to spread as well. It is now prevalent in many Philippine banana plantations. Scientists are trying to modify the banana plant to make it resist Panama disease and are combing remote jungles searching for new wild bananas.

In the CFARBEMPCO coop Tropical Race 4 was initially seen in 2012 and confirmed cases were recorded starting in 2015. The infection of the dreaded disease was quite slow during the initial years, but spread significantly in 2018. After production of Class A bananas rose to 4610 boxes per hectare in 2018, it fell to 3879 in 2019, directly affecting the economic wellbeing of its members. Income of farmers is also affected by the high cost of preventative measures, including fencing the farm and chemical decontamination stations, training farmers and managers, and obtaining seedlings resistant to the fungus.

While the percentage of land lost to Fusarium wilt in the four alliance coops is still small, other coops affiliated to FARMCOOP in neighboring regions of Mindanao have been devastated, with the CASAMA coops losing two-thirds of their productive area and one, TCBC, losing all of it. These coops have tried to recover by planting other crops.

Fungicides and chemical agents are not considered very effective against Fusarium wilt, so quarantining fields and sanitation is a common answer. Chemical stations stop everyone on the roads leading into the Davao plantations. As trucks, cars and motorbikes pull up, a sanitation worker sprays chemicals on the tires and underside of the chassis. Passengers get out and walk through a bath of fungicide to kill contaminants on the soles of shoes and flip-flops.

The sanitation stations are also intended to stop the spread of the other banana plant disease, sigatoka. The sigatoka fungus affects the leaves of the banana plant, producing brown spots and black streaks. Eventually the infected leaves start to collapse, and the plant dies. Commercial plantations have mostly treated the disease by applying fungicides. While it doesn’t save plants that are heavily infected, it can stop its development or prevent it. Infected leaves have to be removed, even after spraying, and plants with damaged leaves produce much less fruit. Resistant strains of sigatoka have begun to appear, as well.

Another pesticide, Lorsban, was historically used on some plantations, especially those in the Compostela Valley two decades ago, to control banana scab moth, banana weevil borers and caterpillars. The pesticide was applied by coating the plastic that surrounds the bunches, so workers in the groves were exposed to it,and even children who worked in the packing sheds flattening the used plastic sheets for recycling.

Monocrop banana cultivation has had a high environmental cost from the beginning of its development. In Maragusan, in Mindanao’s Compostela Valley, one worker described what happened when Stanfilco convinced the local people to acquiesce in allowing it to set up a banana plantation. “There used to be many kinds of trees here, marang, jackfruit, mango, pomelo” he recalls, in a report for the Center for Trade Union and Human Rights and the Nonoy Librado Development Foundation. “It was full of forest before… There were also plenty of animals, monkeys, wild boars, birds. Now, there are none. Even frogs cannot survive the banana farms.” Another remembers, “Before, this place used to be forested, there were many trees, and coconut trees…. carabaos, cows, monkeys. Now they’re gone.”

As they develop, the plantations exhaust the soil quickly, requiring inputs of fertilizer to keep them productive. Commercial banana plantations therefore rely on the application of chemical fungicides to control disease, and chemical fertilizer to keep the soil productive. According to Teodoro Tadtad, former manager of DARBMUPCO, “Now that lands are depleted, the challenge for us coop leaders is the improvement of our lands, the capability of the soil to produce.” However, according to the Center for Trade Union Rights report, “This dependence on monocrop plantations is dangerous for future generations as massive degradation of soil can lead to unproductive yield and thus become unsustainable. It also puts into peril the region’s food security.”

A girl in the Compostela Valley flattens plastic sheets coated with Lorsban. Photo copyright © 2020 by David Bacon.

Starting in the 1990s growers began aerial spraying to control black sigatoka, justifying it by claiming that the 83,840 hectares under export banana cropping make it the second largest export crop after coconut oil. Bananas provide 335,372 direct and indirect jobs and pay 6.5 billion pesos (about $142.86 million US) in taxes. A 2006 study, however, by the Department of Health found that aerial spraying of pesticides was having negative effects on the health of residents, and the following year Davao City passed an ordinance prohibiting aerial spraying. The Pilipino Banana Growers and Exporters Association, Davao Fruits and Lapanday Agricultural Development sued the city, and the Supreme Court declared the ordinance unconstitutional in 2016.

The FARMCOOP cooperatives were torn, and issued a statement that “Since proponents of the ban did not offer an alternative, ground spraying … seems to be the only alternative to aerial spraying. … Ground spraying is less efficient, consumes 85% more water, is more costly and harmful because it brings inorganic fungicides closer to the ground, waterways, roads, buildings and people. … The true issue is not the method of application, but the material that is applied for sigatoka control. The key to do away with the problems posed by aerial spraying is the availability of safe fungicides – organic fungicides. … The ARB Cooperatives thus urgently call on the government and the private sector to facilitate scientific research to develop not only effective organic fungicides but also other bio-pesticides to encourage organic or less chemical production of exportable bananas.”

Just a few years after getting rid of the onerous contracts, FARMCOOP began urging its member coops to begin exploring organic farming, partly because of the rising issue of sustainability, but also because of changes in the international market for bananas. As early as 2002 the coops’ marketing arm, FEDCO, brought buyers in from Korea, Japan and China, and negotiated sales contracts for both Class A and Class B bananas. “FARMCOOP urges FEDCO’s member coops to start transferring their plantations to organic farms where no chemicals or pesticides are used. In the next ten years demand for lowland bananas will fall in Japan. Today more and more Japanese consumers are looking for organic bananas grown in the highlands, on cool mountain slopes,” according to Koronado Apuzen.

FARMCOOP itself started its first five-acre farm of organic bananas in 2002 – Mindanao Organic Ventures Enterprises, in Maligatong, in Davao City. The organization developed a protocol for transition from high-chemical to low-chemical farming, and implemented it on this farm. “The objective of this protocol is to verify and develop technologies for the conversion of conventional banana farms from high-chem to low-chem and to organic and finally to natural banana fruit production. It also aims to drive ARB coops to become competitive in the production of low-chem, organic and natural bananas for the world market.” Coops were encouraged to set aside areas for experimentation in collaboration with FARMCOOP’s research and development unit.

Since then more experimental plots have been set up connected to the ARB coops, to compare hi-chem and low-chem production. Dr. Modesto Recel explained, “We’re doing this gradually and hoping our partner-coops will see the wisdom of reducing the use of chemical fertilizer and synthetic pesticides. Ultimately we want them to use environment-friendly organic farm inputs to save Mother Earth.” A set of plots set up in 2015 went from gradual reduction of chemical fertilizers by 25% in the first year, another 50% the second year, 75% the third year and 100% the fourth year. The chemical fertilizer was replaced by Living Soil, the FARMCOOP-produced brand of compost fertilizer.

New Indigenous Coops in Sibulan

In 2004 FARMCOOP began a new project—setting up organic farming coops among indigenous Bagobo-Tagabawa farmers on the slopes of Mount Apo, near Davao City. The project not only helped to provide a new testing ground for organic agriculture, and a way to spread cooperative systems, but also marked an important step in the revitalization of rural life in an area that had been decimated by armed conflict.

Jimmy Ancia, who today is manager of the Sibulan Ancestral Domain Organic Cooperative (SADOPCO), remembers that “During the 1980s there was a lot of armed conflict here, with the government Battalion 3646. The army couldn’t relate to civilians. In one incident, they burned 57 houses and killed people. That’s why some people went over to the other side.”

As a result, many families left the area. The local economy, which had mired residents in poverty for years, became unable to sustain the local community. Bagobos began to fear the loss of their history and cultural traditions. “But after 1993 people started to come back,” he says. “We’ve had the military here now for 18 years. The other side sometimes passes through too. But the fear has decreased. There’s been only one conflict in the last two years. Some are still fearful, though, and haven’t returned yet. But people aren’t afraid to work in the forest any more, which they were before. And in the virgin forest we don’t let anyone cut trees or farm.”

The Sibulan barangay has only 250 hectares of arable land, 600-1000 meters above sea level, 40 kilometers from Davao City. That land has to support 4,125 residents in 513 families, giving each family only 1-5 hectares to sustain it on farms that were historically rain fed, and used traditional methods of land preparation. Per capita income was less than 36,000 pesos/year ($720 US) – far below the Philippines’ poverty line.

Poverty places the Bagobo-Tagabawa tribe in a precarious situation. Most households do not have electricity and use kerosene lamps for light, and get their water from springs. Only 3% of Bagobos have gone to college, while 55% finish elementary school and 43% graduate from high school. Because they lack formal education families can’t open bank accounts, and therefore are excluded from access to formal capital to improve their farms.

In 2004, therefore, the tribe decided to make a plan for economic development that could give families a better future. According to Carlos Salinde, who today leads the Pamara Producer Cooperative of Organic Banana Growers (PAPCOBAGROW), “The big companies had agents everywhere, trying to entice us into developing banana plantations. But the barangay got upset when they started offering money to buy people out. We decided to have a meeting with representatives of the companies and attorney Apuzen, and they all presented their plans.”

Apuzen recalls, “We got an invitation from Sibulan to attend a meeting of the farmers and to present our program. The big banana companies did the same. Stanfilco was there. Lapanday was there. AMS Corporation was there. I was the sixth and last speaker, and I told them,” We will help you grow organic bananas, so we will not be using pesticides or chemical fertilizers. Your environment here, the forests, will remain, unlike what happened in other places where they have no more trees. We will not cut trees. We will plant bananas only in open spaces. You will become growers and your bananas will enjoy a good price, being organic.’”

“When our tribal community agreed to have FARMCOOP come in we were attracted by their respectful organizing methods,” explains Fortunato Tungkaling, a member of SADOPCO’s Board of Directors. “They also agreed not to cut trees, which is very important to our culture. With the other companies we would have had to lease our land, and the trees would have been cut down to make plantations.”

Apuzen adds, “After two weeks they sent a message saying they preferred FARMCOOP over the others. When they decided that, we had no buyer. We had no money. We did not have the technology. Even some of my staff said, ‘Why did you accept their invitation and present organic production?’ I said, ‘Look up – somebody there will provide.’” So FARMCOOP launched the program: Sustainable Agriculture and Market Access for Indigenous People and Agrarian Reform Beneficiaries Towards a Better Quality of Life.” And money did come,from CORDAID from the Netherlands, and later from other sources.

Barangay Sibulan is among the few remaining upland communities in Davao City that remained untouched by the invasion of monocrop and chemical-based banana production. With land suitable for growing super-sweet highland bananas the project offered an alternative to marginalized small farmers in Davao City’s watershed areas. “But when we started there was no infrastructure in Sibulan and no services in those communities,” Apuzen says. “There was no road to most of them, and when we set up the first packing shed people had to bring in the bananas on horses. We got a million peso grant to bulldoze a road and put lime on it donated by Holcim Cement Company. It still cost a million pesos to pour concrete for just 100 meters of road.”

At the same time, six banana coops and individuals formed the Organic Producers and Exporters Corporation (OPEC), to provide organic and low-chem food products access to domestic and international markets. Its first project was marketing the highland organic bananas produced by the people of Sibulan. OPEC found a buyer in Japan, telling it that “highland organic exportable bananas will be intercropped with coconut and other fruit trees. To comply with the international requirements for organic certification the farmers will apply only botanical pesticides, organic fertilizers and other processes compatible with organic farming.”

In 2006 the Sibulan Organic Banana Growers Multi-Purpose Cooperative (SOBAGROMCO) and the Pamara Producers Cooperative of Organic Banana Growers (PAPCOBAGROW), another Sibulan banana coop, got organic certification from the German ECOCERT and the Japanese Agricultural Standards. After certification the Japanese buyer increased its price by almost 80%, and asked for 3 containers/week. In 2014 SOBAGROMCO received organic certification from Woorinong in South Korea, and the Organic Certification Center of the Philippines. It now has the USDA organic certification as well.

“The banana project has been a huge help for us,” explains Annie Ontic, SOBAGROMCO manager. “Before, we had no jobs and no work. With the introduction of the project the coop now provides work to the community. You no longer have to leave to find work. There are now 27 motors [small motorcycles] here, and before we couldn’t afford any. And we’re sustaining this with training and education.” FARMCOOP helped set up eleven savings and loan associations to give farmers access to credit.

Nevertheless, she says, it was very hard getting the coop started. “We used horses to transport the bananas, so a lot were bruised and were rejected. Now we borrow trucks from FARMCOOP. We still have a lot of difficulty because of the lack of decent roads, and the coop and the barangay are trying to get support for more. The barangay really has no money for it, so in the meantime we have the tradition of bayanihan. That means that collectively we participate and contribute labor to projects we need. We can mobilize ourselves to make roads, and the coop can pass resolutions to ask the government for help.” Two coops give 3¢ per box to the barangay, and 2¢ to the tribe, as well as money for other projects in the community.

FARMCOOP helped the Bagobo Tagabawa in the ancestral domain to set up a coop to grow coffee and cacao—SADOPCO—providing seedlings, compost, and technical help. Some 262 families are members and more want to join. “Families can now send their kids to school,” says Tungkaling. “The terrain is steep, and it’s cooler because the farms are at a higher elevation, which is a good environment for coffee and cacao. Bananas aren’t feasible here. The roads are poor, and the fruit would be bruised getting it to a shed.”

As important to the Bagobo Tagabawa as their economic improvement was the impact on their culture. “Our strongest relationship is through our culture, and the whole tribe participates,” SADOPCO’s manager, Jimmy Ancia says. “We’re bringing back the organic way of farming, and protecting our ancestral domain. Coffee and cacao play an important part in traditional culture, and we produce coffee for our own consumption. We have a saying, that if you don’t drink coffee, you’re not a Bagobo.” Women are represented in the leadership of all the coops, and manage one, and provide non-violence training to coop members.

According to Ethel Apuzen, a nurse and veteran political activist who works with Koronado Apuzen on the Sibulan project, “This barangay is part of the city, but never got healthcare services or clinics. There was no doctor until three years ago, and the first clinic only opened last year. Our emphasis is preventive, versus the government’s curative approach. Bagobo Tagabawa have indigenous practices, curing minor aches and problems with massage and indigenous herbs, and some people here are traditional healers. We try to introduce new techniques, but we’re careful to add to what the community already has.”

The Sibulan project also involves agro-forestry – planting indigenous and fruit trees on slopes of rivers and as boundaries of farms, serving as buffers and windbreaks, preventing erosion and protecting the watershed of Davao City.

Emilyn Janolino, a Bagobo FARMCOOP Project team member in Sibulan, says tribal members have learned about indigenous micro-organisms. “We see the difference between plants that get compost alone, and those that get compost and microorganisms, and we’re starting to make our own concoctions.” When the Sibulan coops were organized, FARMCOOP developed an area to begin producing fertilizer, as well as a model organic farm to demonstrate organic farming techniques. It coordinated indigenous seed-saving, and established seven plant nurseries and eight vermi-composting facilities.

By 2008 the need for compost had grown, and for a larger area to begin processing bananas into banana-based food products like banana puree, catsup, jam and vinegar. Near the lowland coops FARMCOOP set up Ecopark, the second Bio-Organic Fertilizer and Pesticide Complex. Ecopark has a production and processing area for compost and and Korean Natural Farming fertilizer. It has a facility for drying banana slices and grinding them into banana flour. The complex contains a laboratory for research, food processing and tissue culture. On the ground floor of the FARMCOOP office in Davao City the organization set up a ripening room to serve local banana buyers, and the fruit is now sold in major urban shopping centers and malls.

Two years ago a convention of small Mindanao coconut farmers also asked FARMCOOP for help, and formed an association of cooperatives with 2,000 families on 2,300 hectares of farms. Coconuts are the most widely-cultivated crop in the Philippines, and a third of the population is dependent on growing them. Yet coconut farmers are among the poorest. “Our objective,” says Ricardo Paulmitan, FARMCOOP’s coconut organizer, “is to raise the farmers’ income through making maximum use of what they produce, like coconut water or flour, and sell products that have a higher added value than the raw coconut itself.” In July, FARMCOOP with the small coconut farmers’ association and other stakeholders broke ground at Ecopark for a facility that will process coconut products, like virgin coconut oil, flour, coconut water and coco shells into material for composting and erosion control, allowing Ecopark to supply the banana, cacao and coffee producing coops with much more compost than it does at present.

According to Kahlil Apuzen-Ito, FARMCOOP’s technical advisor, the guiding principle in this activity is the promotion of permaculture, the term for permanent agriculture. “This is a cyclical and natural pattern in agriculture, in a land use and community building movement that strives to harmoniously integrate human dwellings, microclimate, annual and perennial plants, animals, soils and water into stable productive communities.” Through the Sibulan project, FARMCOOP saw an opportunity to advance a positive policy environment, presenting organic farming technology as a model that can be embraced and adopted among producers of exportable bananas in Mindanao.

Conclusion

The People Power Revolution that brought down Ferdinand Marcos created the political will for passing a land reform law that was much more radical than the ineffective and in-name-only mandates of the previous four decades. The law in turn created the opening for plantation workers to gain control of land and use it to change the material conditions of their lives.

But the experience of those workers, and the cooperatives they established, make it obvious that the law by itself was not enough. It was only when banana workers organized and struggled against the obstacles created by multinational corporations and wealthy landowners, that they were able to free themselves, at least partially, from the system that had held them in poverty.

In The Politics of Counter-Expertise on Aerial Spraying, Lisette J. Nikol & Kees Jansen assert that, “export banana production is jointly controlled by multinational corporations … and local landed elites, including the Philippine banana producing companies LADECO, TADECO and Davao Fruits, owned by the Lorenzo family, the Floirendo family and the Soriano family, respectively [through] the Pilipino Banana and Exporters Association (PBGEA) which operates like a cartel, controlling price levels of labor, land lease rates, and farm input and output markets.”

The lowland coops in Davao, however, had a history of militant trade unionism and organizers who understood that a resource center, FARMCOOP, would be necessary to succeed. The coops they helped organize staged their own version of People Power by refusing to produce and deliver bananas to Stanfilco for two months, suffering severe economic hardships, harassment and brutality from company goons, security guards, policemen and soldiers. Two farmers were shot and wounded.

But the outcome of that watershed event was the ability of the coops to negotiate contracts that made large changes in their standard of living, and which made it possible for other groups of plantation workers to do the same. FARMCOOP has become a brain trust, a strategy and resource center, supporting workers and farmers using the agrarian reform law. This has given many of them an alternative to becoming targets of the multinational corporations and their Philippine partners, who prowl for land to lease at minimal rentals, and for a low-cost workforce to provide the necessary labor. At the same time, FARMCOOP has called for alternatives to the unsustainable and environmentally destructive farming technology perpetuated by those corporations.

Alvee Mabong packs bananas for Unifrutti in the DARBCO packing shed. Photo copyright © 2020 by David Bacon.

The watershed plantation strike of 1998 eventually created as well the possibility for building cooperatives among indigenous communities, replicating the success of cooperatives in the conventional banana plantations in the lowlands among Bagobo-Tagabawa farmers in the highlands of Sibulan. That development may not only affect the economic situation of banana farmers, but may also create a base for organic agriculture in the banana industry.

“We are responding to the challenging realities of rural underdevelopment in the backdrop of rapid environmental degradation,” explains Kahlil Apuzen-Ito. “FARMCOOP seeks to strike a balance between rural economic growth and consolidating and mobilizing indigenous communities as primary stakeholders and stewards of their farms and environment. We face the continuous encroachment of multinational corporations into the heart of watershed areas of Davao City, displacing indigenous people from their ancestral domains. We are organizing a sustainable and profitable farming model to provide an alternative for these indigenous farmers to the stranglehold of multinational corporations and their mono-crop and chemical-based farming schemes.”

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.