The People Went Walking: How Rufino Dominguez Revolutionized the Way We Think About Migration Part I

This publication was edited by Luis Escala Rabadan.

This publication is the first part of a three part Issue Brief on the life of the radical organizer, Rufino Dominguez. This Issue Brief is part of Food First’s Dismantling Racism in the Food System Series. This Issue Brief has also been translated into Spanish.

Click here to download the PDF version in English.

Introduction

It is a great pleasure for the members of the Binational Central Committee of the Indigenous Front of Binational Organizations (FIOB in Spanish) spread across Oaxaca, Baja California and California, to present readers with the life history of one of the founders of our organization in this piece, entitled “The people went walking: How Rufino Dominguez revolutionized the way we think about migration,” written by independent journalist David Bacon, a longtime ally of the FIOB. This editorial effort is a collaboration between FIOB and the Institute for Food and Development Policy/Food First.

Our movement and struggle for justice and the rights of the original peoples of Mexico and for the human rights and labor rights of indigenous migrants in Baja California and the United States has been constructed over many years with the participation of many people. When he sat down to speak with farmworkers along the edges of the immense fields where he organized improvised meetings, Rufino Dominguez used to say “One person alone doesn’t create a movement of struggle.”

Nonetheless, of the many activists that have made up our movement, our compañero Rufino Dominguez is one of the most important. For all of us who worked closely with him, he was a leader who inspired us with discipline, dedication, and love for our struggle. As David Bacon points out in his piece, Rufino began his activism at a young age, adapting his organizational forms of struggle to the different contexts along his migratory route: Culiacan and San Quintin, Mexico, and the Central Valley of California. Long before our organization was founded, he was thinking of the different ways that our people could resist the enormous problems and challenges we faced in our communities of origin, and in the different points that poverty and marginalization forced us to migrate.

Rufino’s own experience as a Mixtec, as an indigenous person and as a migrant laborer, helped him formulate organizational proposals with a broad vision because his objective was always to be an effective political actor in Mexico as well as the United States. His goal was not modest: to struggle transnationally for the right not to migrate and to have a dignified life in our communities of origin, and at the same time to struggle in defense of the rights of migrant people wherever they found themselves.

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

Sign up today!We hope that by publishing this biographical semblance of Rufino Dominguez, many more migrants and our sisters and brothers in our communities of origin learn more about the history of our organization and the ideas that guided his struggle. We want this publication to be used by the local committees in Oaxaca, Baja California and California to raise the political consciousness and kindle the popular indigenous resistance struggles that we so badly need in Mexico and in the United States.

We also want the allies of our movement to know the people that have made the consolidation of our movements possible, and learn about the political, ideological, practical and organizational contributions of leaders like Rufino Dominguez, so that together we can develop strategies that help build a better world with justice and dignity for all, including the indigenous peoples and migrant laborers on both sides of the conflictive border between the United States and Mexico.

“Never again a Mexico without us!”

“For the respect of the rights of indigenous peoples”

The Binational Central Committee of the FIOB

The People Went Walking: How Rufino Dominguez Revolutionized the Way We Think About Migration

It is a bitter irony that when it was time to bury Rufino Dominguez, his own community of San Miguel Cuevas initially refused him a place in its pantheon. In the end, the town’s communal leaders relented, but by then it was too late. His body was already on its way from Fresno, California, to its final resting place in Paxtlahuaca, the hometown of his wife Oralia.

It’s hard to imagine that Rufino would not have cared deeply. His commitment to the indigenous culture of the place where he was born, in Oaxaca’s Mixteca region, guided his life’s work. Yet Rufino had long since chosen to serve the larger concerns of the entire migrant exodus from southern Mexico over his own town’s requirements for remaining a comunero in good standing. That choice enabled him to shape the political thinking of an entire generation of migrant activists in Mexico and the U.S. But it came at a high price.

Like many Oaxacan indigenous towns, San Miguel Cuevas has a system of cargos, or community responsibilities, that provide the structure for its economic, social and political life. The obligation of the “tequio” allows the town to require work from its residents. In an era in which many, if not most, of those residents live as migrants thousands of miles away, the rule is strict. If you are chosen, you must return in order to fulfill your responsibilities.

Rufino himself recognized the value of this tradition. “We use the tequio, the concept of collective work to support our community,” he told me in an oral history for the book, Communities Without Borders. “We know one another and can act together. For instance, when a community gathers to build a school, the government doesn’t send workers to gather rocks or sand for construction. People from the community do it. They each take turns, carrying 5 rocks or a bag of sand. The whole town is obligated to help, and if people don’t, there are consequences, like going to jail or getting fined.

“Wherever we go, we go united. It’s a way of saying that I do not speak alone — we all speak together. Our people in Oaxaca don’t care if we have been here for 10 years. They send us notices telling us, ‘Rufino, you have to return to serve the community as a secretary, to be a council person or a president.’ Mexican law doesn’t recognize that we, living here [in the U.S.], have political rights and obligations. But in our indigenous communities, we do.”

Rufino’s passionate defense of the tequio and the system of cargos was typical of his lifelong campaign to demonstrate to the rest of the world the value of indigenous Oaxacan culture. But this was not his main contribution to the politics of migration.

Rufino Domiguez’ sense of responsibility went beyond the cargos of San Miguel Cuevas. He inherited the political ideas of the Mexican left, and combined them with the indigenous traditions and culture that developed in Oaxaca long before the arrival of Europeans. He analyzed the roots of modern mass forcible migration. He formulated a new way of looking at migrant communities that sees their crucial importance to the political economy of states like Oaxaca, and to the regions to which they travel, both in northern Mexico and the U.S. And he acted, helping to develop organizations reflecting this new social reality – vehicles for migrant communities to attain self-awareness and to fight for power.

1968, the Dirty War and the CIOAC

Rufino’s generation followed that of the veterans of 1968, who were formed politically by the Mexican army’s attack on an increasingly radical student movement, ending in the worst political crime in modern Mexican history. As students gathered in the dusk at Mexico City’s Tlatelolco Plaza, just weeks before the opening of the 1968 Olympics, soldiers opened fire. Hundreds died. Hundreds more were sent to prison.

Students in Mexico City march in memory of the 1968 massacre. Photo copyright © 2019 by David Bacon.

Four years after the Tlatelolco massacre, in 1972, students and leftwing political groups tried to end the nightmare by marching through the capital’s Centro Historico. Again, activists were carried from the streets covered in blood, attacked by the Halcones, the government’s paramilitary thugs. To maintain control through the 1960s and 70s, the government and the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) organized a wave of repression – the Dirty War. Social movement activists disappeared and were murdered – many whose names are still unknown or unacknowledged.

At the time of the Dirty War the great wave of migration from Oaxaca to the U.S. was still a decade in the future. But already, in central Mexican states like Michoacan, Zacatecas and Jalisco, farmers displaced by poverty had begun a great mass migration. Their home villages in the countryside were stripped of working-age people, leaving just the very young and very old. Political refugees from the Dirty War joined economic migrants on this road to the north. Soon, in Los Angeles, the Bay Area and other concentrations of Mexicans on the west coast, militants in exile gave the growing Chicano movement an infusion of energy and ideology.

This combination was no accident. Leftwing groups in Mexico, especially the Mexican Communist Party (PCM), had begun sending members north, convinced that the expanding Mexican communities in the U.S. could be a natural source of support for the movement back home. In the Los Angeles union locals of the United Electrical Workers, labor leader Humberto Camacho welcomed refugees and gave them jobs as organizers. Political migrants organized other unions among undocumented workers, like the General Brotherhood of Workers, or later, the California Immigrant Workers Association. This powerful combination, which included radicals coming north from Central America’s civil wars, had a profound impact on California, especially on Los Angeles’ politics. Over the next two decades, it transformed the city from the citadel of the open shop to a labor stronghold, and ended Republican Party control.

South of the border, this wave of migrants furnished a workforce as well for Tijuana’s maquiladoras. Soon they began striking to win recognition for independent unions, at Solidev and other factories. Help began flowing back across the border from southern California. Militant PCM members in Baja California, like Blas Manriquez, began seeing this growing population of migrants from the south as a base for political change.

Rufino Dominguez, born on September 4th, 1964, was only 3 when soldiers shot the students in Mexico City, and a boy during the years of the Dirty War. In many ways, San Miguel Cuevas was still a town at the margin of Mexican society. In the 1960s electricity had yet to reach its homes. In later decades the streets would be paved, the church fixed and other improvements made, all paid for by remittances sent home by San Migueleños working in the north. But in Rufino’s first years, candles were still the only light at night.

“Before I was born my mother and father would leave to work in Veracruz, in the sugar cane,” he remembered. “People had no cars, so they went walking, as they used to say. I don’t know how far it was, but my dad would count the days it took to get there. Later, when I was born, they got more established in town and didn’t leave.

“We planted corn and beans, and had fruit trees. My father, Primo Dominguez Tapia, was a carpenter, an artist and a curandero, treating people’s illnesses.” Bonnie Bade, a California anthropologist, studied with Primo Dominguez. She recalls “we documented the names and uses of medicinal plants, ancient diagnostic methods and medicinal treatments, and the underlying concepts of illness and health in Mixtec medicine.”

While San Miguel Cuevas had an elementary school, continuing on to high school meant going to the nearest large town, Santiago Juxtlahuaca. Rufino was recruited by a religious order, the Marist brothers, who ran a boarding school based on the ideas of liberation theology and the preferential option for the poor. “They were like the Jesuits,” Rufino explained. “They showed me a lot of things about life, about our communities. That’s where my social consciousness began. They had a beautiful life, but they didn’t get married, and couldn’t organize, something that I was already becoming passionate about. By then I’d learned that if there’s a problem, it is important to organize the people to resolve it. The brothers spoke about the need to stand up for justice, but they would only talk and not actually do it.”

Mexico was filled with political challenges to the ruling PRI in the late 1970s, especially in the rural states of the south – Chiapas, Guerrero and Oaxaca. Sometimes church radicals and leftwing organizers found themselves on the same side. In “Popular Movements in Autocracies: Religion, Repression, and Indigenous,” Guillermo Trejo notes that “Unlike the struggles of the 1960s and 1970s, in which independent rural indigenous communities petitioned for land without institutional assistance from any external actors, in the late 1970s the Catholic Church and the Mexican Communist Party became major promoters and sponsors of rural indigenous movements [leading to] powerful collective movements for land redistribution.”

Although the Dirty War had driven most urban political activity underground, poverty and land hunger in rural communities continued to provoke rebellions, often led by leftwing organizers. From 1965 to 1975 Ramon Danzos Palomino organized land invasions and campaigns to implement land reform through the Independent Central of Farmers. Then, in 1975 he left to start the Independent Central of Agricultural Workers and Farmers (CIOAC). Both organizations were closely tied to the PCM, of which he was also a leader.

The CIOAC had an indigenous character from the beginning. In Chiapas it was organized by a Tojolab’al farmer from the Plan de Ayala Ejido, Margarito Ruiz Hernandez. Antonio Hernandez Cruz, a CIOAC activist in Chiapas, says in Trejo’s book that “the construction of Tojolab’al autonomy … can be traced back to different forms found in the 1970s, be they unions of ejidos or the CIOAC.”

Rural organizing on the left included the recruitment of teachers. Historically, going back to the Revolution of 1910-20, Mexico’s rural teachers were very often community leaders. They generally opposed the clericalism of the church, and advocated land reform. Under President Lazaro Cardenas, in 1934 the Mexican Constitution was amended to say, “State education will be socialist in character.” Many Communists and radicals worked for the Secretariat of Public Education.

Later, during the Cold War and then the Dirty War, rightwing leaders of the National Union of Education Workers, the largest union in Latin America, purged the teachers’ union of leftwing educators. However, when Luis Echeverria, who as attorney general gave the order to shoot at Tlatelolco, became President, he sought to soften the government’s (and his own) harsh image. Mexico’s official policy of discouraging indigenous languages in school was ended. A new wave of bilingual teachers began working in rural areas.

Trejo adds that rural organizing was tied to “recruiting bilingual indigenous teachers trained by the state, and local leaders … carefully selected and trained by sending them to Mexico City and abroad, including such places as Cuba, Nicaragua and the former Soviet Union.” Many of these dissident teachers, including Communists, organized a leftwing caucus within the union, the National Coordination of Education Workers (CNTE). By the 1980s they had won control of the state unions in Chiapas, Oaxaca, Guerrero and Michoacan. In this bloody struggle over 100 teachers were murdered in Oaxaca alone.

Finally President Echeverria lifted the illegal status of the PCM and other left parties. In 1976 four of them united in the Coalition of the Left to run a railroad union leader, Valentin Campa, for president.

Rufino’s Birth as an Activist in Oaxaca and Baja California

In 1980, in the midst of this political effervescence, Rufino Dominguez entered the preparatoria, a school in Tlaxiaco that funneled students into Oaxaca’s “normales,” or teacher training schools. According to Gaspar Rivera Salgado, a Mixtec professor at UCLA who worked with him for many years, “Rufino found a traditional left environment in this prepa run by the normales. He was only there for six months, because the school went out on strike and the students shut it down. He used to joke that otherwise he would have become a teacher. But even then he was elected president of the student body.”

Laura Velasco at Tijuana’s Colegio de la Frontera Norte interviewed Rufino several times for her books on the Oaxacan diaspora. “Rufino told me that he was a militante in the PCM when he was 16,” she recalls. “It’s where he got his vision of class, that indigenous people and migrants are people who are exploited economically.” Some of that ideological training Rufino also got from Ernestino Sixto Chávez, a radical teacher who owned a small shop fixing radios and televisions in Juxtlahuaca.

In 1980 the PCM won its first election victories – the municipal presidencies of the small towns of Alcozauca de Guerrero in Guerrero state, and Tlacolulita and Magdalena Ocotlan in Oaxaca. The following year the Coalition of Workers, Farmers and Students of the Isthmus (COCEI) won control of the municipal government of Juchitan de Zaragoza, one of Oaxaca’s most important cities. By then, the PCM had organizationally merged with its partners in the Coalition of the Left, and formed a new party, the United Socialist Party of Mexico (PSUM). In the new Juchitan city council, the PSUM held two of the seats.

COCEI’s victory electrified Mexico’s left. The new government ran literacy programs for a town in which 80% of the people couldn’t read, purged corrupt police, fixed roads and the municipal market, and built new health clinics. “In those years COCEI was very strong in Oaxaca,” Rivera Salgado recalls. “Here Rufino began trying to adapt the traditional radical ideas of the Mexican left, including the ideas of Marx, to the struggles of indigenous people.

“COCEI itself held its meetings in Zapoteco, although they didn’t yet have a word in Zapoteco for class struggle. People were so proud of who they were. At this time PSUM was becoming a legal party, and Rufino was part of that. But because of the strike he’d lost his fellowship and couldn’t survive without it. He went back to his community, and began to fight to get rid of the cacique [town boss].”

That cacique was Gregorio Platon, the Deputy for Communal Property in San Miguel Cuevas. That position gave him control over communal town lands, and enabled him to fine town residents who’d had to leave to look for work elsewhere – as much as 15,000 pesos. “Those who didn’t pay were put in jail or were threatened with being kicked out of the town,” Rufino remembered. “He burned five homes, and killed three people, including a friend. That’s why I did something, because it hurt me. After two years we were able to get him out of there.”

On October 30, 1983, Rufino and his fellow activists organized an occupation of the town hall, but were then confronted by Platon and his supporters, carrying guns. They were forced into the building, where they were tortured for four hours. Rufino’s father gathered the town’s residents and they marched on the town hall. “We were rescued by the town – otherwise we wouldn’t be alive today,” Rufino recalled. “That’s where my struggle really began.”

Living in Oaxaca was still dangerous, however, and Rufino had just gotten married. With his new wife he took the road north, first to Sinaloa, where thousands of Oaxacan migrants made up the workforce on giant plantations growing tomatoes and strawberries for the U.S. market. The PSUM and CIOAC had already sent organizers there to fight to change the worst conditions in Mexican agriculture.

The export farms of Sinaloa and Baja California were, and are, plantations – giant fields on the scale of the industrial agriculture of California’s San Joaquin and Salinas Valleys. Export plantations were a product of the turn in Mexico’s economic development program in the years after Tlatelolco.

In the early 1970s a generation of technocrats in the PRI began reducing the state sector and reversing the nationalist direction of Mexico’s economy. Beginning with the Border Industrialization Program of 1964, the barriers to foreign investment were taken down in a series of economic “reforms.” Foreign-owned factories – maquiladoras – were originally allowed to operate near the border, using a low-paid workforce to produce for the U.S. market. Eventually the geographic restrictions were eliminated, and maquiladoras spread throughout Mexico.

Mexico’s increasing foreign debt to U.S. and European banks became a lever to enforce a neoliberal development model. Instead of an economy producing for consumers in Mexico, whose jobs and income might enable them to buy what was produced, the economy instead encouraged foreign investment in enterprises producing for foreign (especially U.S.) markets. That gave the Mexican government a stake in keeping wages low enough to attract investment and to keep Mexican products cheap in the U.S.

The consequences for indigenous people in southern Mexico were enormous. Any commitment by the government to maintaining high farm prices was gradually reversed (and later abandoned altogether with the North American Free Trade Agreement.) Once people could no longer sell what they grew for a price that paid the cost of growing it, they needed to seek alternatives to farming in their home communities. That meant migration. As people were displaced by economic crisis, a mobile low-wage workforce mushroomed.

The giant farms developed in the 1970s in Sinaloa, Sonora and Baja California were like maquiladoras, producing for foreign markets, and needing the same cheap labor. But they were located in low population areas. Growers, often partnerships between Mexican landowners and U.S. investors, required a workforce far more numerous than the local population.

The relatively small migration of the era when Rufino’s father went walking to Veracruz was transformed. Recruiters throughout Oaxacan villages filled trains and busses with thousands of people who could no longer make a living. “The living conditions in Mexico were at their worst moment,” Rufino recalled. “That is why during that time many families came with their wives, even their children. This was never seen before.”

Jorge and Margarita Giron left Santa Maria Tindu in Oaxaca to work in Sinaloa in the late 1970s. “We lived in labor camps made of steel sheets,” Jorge remembered. “During the hot season it was unbearable. The roof was flimsy and when it rained everything got wet. We would put everything up on a table to avoid having things swept away by the water, which would even take bowls and pans with it. In the morning we would huddle around the foreman and he would give us buckets for the tomato harvest. When they were irrigating, we took off our shoes and went into the fields barefoot, even if it was freezing. Going in like that made us sick, but there were no rubber boots. We worked from sunup to sundown. Candlelight was our only form of light. The towns and cities were far away. We could only go there on Sundays, so the camps provided everything. There was a store that gave us food on credit. On Saturday we would get paid and pay our debt.”

His wife Margarita recalled that in the fields “when you had to relieve yourself, you went in public because there were no bathrooms. You would go behind a tree or tall grass and squat. People would bathe upstream while downstream others would wash their clothes, and even drink the water. That’s why many came down with diarrhea and vomiting. Others drowned in the river because it was very deep. The walls in the camp were made of cardboard, and you could see other families through the holes. In the camps you couldn’t be picky.”

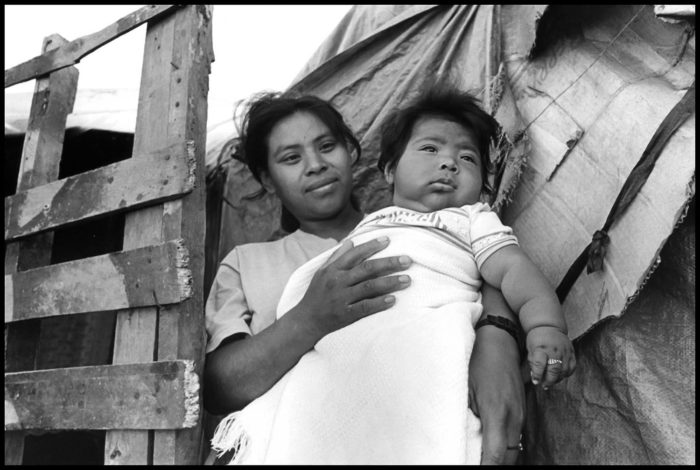

Isabel Zaragoza and her infant daughter Lagoberta in a labor camp in Vicente Guerrero, in the San Quintin Valley.

In the early 80s students came out to the camps from the University of Sinaloa in Culiacan. CIOAC sent organizers from Oaxaca, like Benito Garcia, a Mixteco from San Juan Mixtepec. Together they organized strikes. “When the students came we would leave the fields and stop working,” Jorge Giron remembered. “Then the police would come and take away the students. We wanted workers’ rights, better salaries and jobs, better housing, running water, and transportation to and from work. Eventually the bosses began to cut the workday to eight hours, and when they needed a couple of extra hours they paid double. Before, if we worked ten or eleven hours, we were paid the minimum. After that movement, things got better.”

Rufino met the CIOAC organizers, especially Benito Garcia. “I saw a lot of discrimination towards indigenous people,” he remembered. “The bosses would shout at them, ‘you donkey, put your back into it!’ I began to organize the people from my town that were working there. They asked me to set up a meeting to talk about what had happened [with Gregorio Platon] in San Miguel Cuevas, and what I had done. Then we decided to set up an organization outside of the political parties, the Organization of Exploited and Oppressed People (OPEO), with help from CIOAC. Benito helped us come up with a symbol for the organization and got our flyer printed, and we supported the marches and strikes he organized. I worked very closely with him.”

Velasco says that in OPEO Rufino was combining two ways of looking at the people he was organizing. “They were oppressed because they were indigenous, and they were exploited as workers,” she says. “He didn’t call it a political front or coalition of other organizations, but an organization of people themselves.”

It was unique and new in other ways as well. Indigenous migrants ran OPEO according to rules and principles they themselves adopted. It had no paid staff – not in Mexico, nor later in the U.S. Its purpose was to fight against injustices perpetrated against people as migrants, in the areas where they were working and living, as well as to deal with the problems back in San Miguel Cuevas.

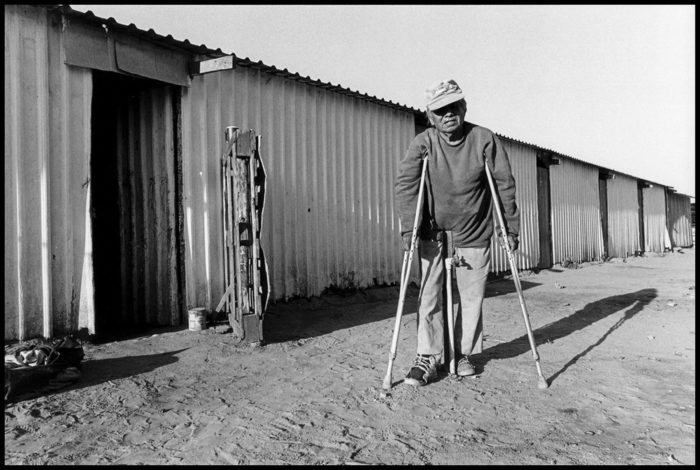

Marcial Sayas Flores, a disabled farmworker living in a labor camp in Vicente Guerrero, in the San Quintin Valley.

It was new also in the sense of what it was not. While it was part of the left, and worked with leftwing organizations, it was not the creation of a leftwing political party. And while it organized workers to fight, even to strike for better wages and conditions, it was not a union.

“In his thinking we see the combination of three big ideas,” adds Rivera Salgado. “From the Maristas he got the ideas of liberation theology and the preferential option for the poor. You can see their influence in the way Rufino believed you have to dedicate your life to your ideals. In the traditional left he found a class-based way of looking at exploitation, and the need for organized social resistance to it. And from his own community he took the ideas of identity, obligations and responsibility, and the collective way of making decisions.”

Rufino dated his turn to questions of indigenous identity to his experiences in Sinaloa and Baja California. “During that time when I first began, I didn’t know what being Mixteco was,” he explained in his oral history for Communities Without Borders. “I didn’t know why they were calling me Mixteco. I didn’t know how to appreciate what I was, what I spoke, or what I had. I didn’t know what it was to be indigenous. When I went to high school in Juxtlahuaca, away from the town where I’d grown up, the girls would laugh and I felt embarrassed. I thought, ‘I’m going to stop speaking Mixteco because they laugh at me. I’m going to stop walking next to my mother because she dresses in traditional clothes.’ Many of us stopped speaking our language and denied being indigenous. It wasn’t our fault. It was the racism from the mestizos and the lack of education.

“We began to understand this in Sinaloa, and when I arrived in Baja California, we continued because they’d call us Oaxaquitos or Oaxacos or Indians. They’d tell us we were ignorant, and I realized that they were making me feel different. During that time I felt scared. There wasn’t much talk then about an indigenous movement. We were very isolated. We weren’t in the news; we didn’t exist during that time. In addition, [during our strikes] we were accused of being involved with the FMLN of El Salvador, manipulated by the commanders of Central America. The bosses said we were foreigners. We’d tell them, ‘How can we be foreigners if we’re from Oaxaca, in our own country?’

“Now I speak my language in front of people, and I don’t feel embarrassed. I am a human being like everyone else. I know my identity and I’m proud of it. I know I am Mixteco or a ‘Nusami’ as we say in our language, and that all of us are important. I appreciate who I am. If someone calls me Native or Oaxaquito or Oaxaco I respond, ‘Don’t say that, I am Oaxaqeño and a human being – just like you.’”

Later in 1984 Rufino crossed the Gulf of California to the San Quintin valley on the Baja California peninsula. There he found conditions that were just as bad. “So I sent Benito a letter to come because there were so many problems. And he came.”

According to human rights activist Victor Clark (in “De Jornaleros a Colonos,” by Laura Velasco, Christian Zlolniski and Marie Laure-Coubes), the Mexican newspaper Zeta published reports of people living outside under trees or making their own shacks out of pallets or other discarded materials from the ranches. After complaints to the state government, growers built the first labor camps, but according to PSUM leader Blas Manriquez, “the foremen and supervisors with guns in their hands don’t let anyone in who appears to be an outsider, thinking they’re agitators.” Repression and violence got so bad that in 1987 CIOAC appealed to the governor to disarm the guards.

Natalia Bautista, who fell in love with Benito and later married him, remembers that her father used his house for the meetings because they all came from San Juan Mixtepec. “They had organized workers in various camps, painting signs, making banners and planning a grand march. Lots of people came from Ensenada and Tijuana over to the house. Now as an adult, I realize the majority were from the PSUM.

“On the day of the march nobody worked. The strike was huge and spread through Vicente Guerrero [a town in the San Quintin valley]. In the labor camps they agreed that nobody would show up for work, and if someone did, they would throw tomatoes at them until they stopped working. They were asking for a salary increase, better treatment from the foremen, a set lunch period and buckets that weren’t so heavy. The strike won higher wages and transportation for the workers. Up to then, workers were brought to work in large tomato containers. After the strike they were transported in buses.

“The political party established itself with the workers after the strike, and worked in support of the union. If there was a work stoppage, the party was there to help. Leaders would speak to the workers about struggles around the world. They spoke of changing the system and establishing a new and different government. I imagined a marvelous place. I guess we’re still waiting for that.”

Click here to download the PDF version in English.

The second part of this three part Issue Brief will be released next week.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.