The People Went Walking: How Rufino Dominguez Revolutionized the Way We Think About Migration Part II

This publication was edited by Luis Escala Rabadan.

This publication is the second part of a three part Issue Brief on the life of the radical organizer, Rufino Dominguez. This Issue Brief is part of Food First’s Dismantling Racism in the Food System Series. This Issue Brief has also been translated into Spanish.

Download the PDF version of this Issue Brief.

Part II

CIOAC survived in San Quintin until the early 2000s, fighting more as the years went by for land on which migrants from Oaxaca could build houses and settle permanently. Benito Garcia was eventually expelled, however, and from the PSUM as well. Rufino organized OPEO, and helped CIOAC in San Quintin, through 1984. Then he left with his wife for the other side of the border. By then his first son, Lenin, had been born in San Quintin.

“I got married in 1983, although I didn’t want to,” he remembered later. “I wanted to devote my life completely to organizing. We need to organize and it demands a great deal, but if you have a family you can’t dedicate yourself completely to this commitment. Once I got married, I had to come to the U.S. because it wasn’t fair to ask my father to keep supporting me and my wife. So I got married and decided to seek my future here.”

In California, Indigenous Migrants and Farm Workers Begin to Organize

Once he arrived in Selma, California, he found that people from San Miguel living there had also heard about his fight to free the town from its cacique, and the strikes in Sinaloa and Baja California. “I felt like I was in my hometown,” he remembered. “People paid off my coyote [the smuggler who helped him cross the border], and asked me to continue my work here. I didn’t even know how to drive, or where the sun rises and where it sets. But we began.

“In 1985 we formed a local committee of people from San Miguel Cuevas. We worked on setting up a clinic back home, as well as playing fields and rebuilding the church. But we were also interested in building up awareness about our need to organize to defend our human and labor rights here. In 1986 I went to Livingston, because it was the center of Oaxacan migrants in Madera County. I started another committee, and began working not just with people from San Miguel Cuevas, but from other towns as well, like Teotitlan del Valle. We set up more committees of the OPEO in Madera and Fresno.”

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

Sign up today!

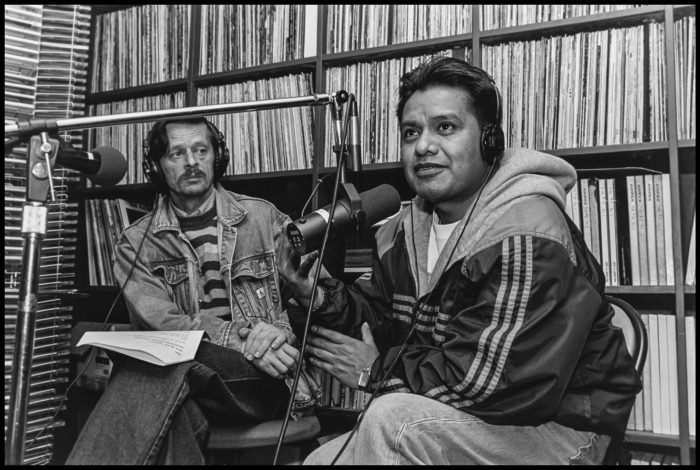

Rufino and journalist Eduardo Stanley on their bilingual program for farm workers on KFCF radio. Photo copyright © 2019 by David Bacon.

In many ways, conditions in California were not so different from those in Sinaloa and San Quintin. “Everyone was a farm worker, and we did a lot about the working conditions. I know them well, because I worked in the fields picking grapes and tomatoes, and working with the hoe. I participated in various strikes in the tomatoes to demand improvements in 1986, 87 and 88. They’d fire me, and then they wouldn’t want to give me any work because they were afraid I’d organize more strikes. I don’t remember how many I participated in, in the tomatoes, and pruning grapes. We were able to force the labor contractors to pay more, but then we’d be blacklisted.

“I worked in the fields until 1991, and then in a turkey farm for a few more years. It was a life of slavery, with no weekends or days off. We worked seven days a week.”

OPEO fought the discrimination against indigenous migrants as much as it did their exploitation at work. “We started one of our first projects in 1986 because many people went to jail because they couldn’t speak Spanish or English. We started an organization of indigenous interpreters, and fought for the legal right in the United States for each person to have translation in court in their primary language. We won this in the U.S., and it’s still something we don’t have in our native country. In Mexico they judge you in Spanish, and they punish you in Spanish. You don’t even know what you did wrong.”

Language discrimination against indigenous migrants reflects a deeper structural racism. The number of migrants from Oaxaca in California, especially in rural areas, began to rise sharply in the early 1980s. By 2008 demographer Rick Mines found that 120,000 migrant farm workers in California had come from indigenous communities in Mexico – Mixtecos, Triquis, Purepechas and others. Together with family members, they accounted for slightly less than 170,000 people. The percentage of farmworkers coming from Oaxaca and southern Mexico grew by four times in less than twenty years, from 7% in 1991, to over 20% in 2008.

In new centers of indigenous population, Triquis, who’d migrated from the same region of the Mixteca that Rufino had left, founded Nuevo San Juan Copala in Baja California. They became the majority of the residents of Greenfield, in California’s Salinas Valley. Purepechas from Michoacan populated huge dilapidated trailer parks in the Coachella Valley, and were packed into garages and tiny apartments in Oxnard.

A third of those workers reported to Mines they were earning below the minimum wage. The median income for a mestizo farmworker family in 2008 was $22,500 – hardly a livable wage. But the income for an indigenous farm worker family was $13,750. In part, the difference reflects the lack of legal immigration status for most indigenous migrants. While 53% of all farm workers are undocumented, according to the Department of Labor, the wave of indigenous migration came after the cutoff date (January 1, 1982) for the immigration amnesty in the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act. When that cutoff date was chosen, it couldn’t have escaped notice by the Act’s authors that Mexico had suffered the “peso shock” later in 1982. The subsequent devaluation of the peso aggravated the existing economic crisis in the countryside, and led to the migration of thousands of desperate families, who crossed the border too late for the amnesty.

Low wages in the fields have brutal consequences. In northern San Diego County, many strawberry pickers sleep out of doors on hillsides and in ravines. Each year the county sheriff clears out some of their encampments, but by next season workers have built others. As Romulo Muñoz Vasquez, living on a San Diego hillside, explained: “ We’re outsiders. If we were natives here, then we’d probably have a home to live in. But we don’t make enough to pay rent. There isn’t enough money to pay rent, food, transportation and still have money left to send to Mexico. I figured any spot under a tree would do.” And San Diego is not the only California county where workers live under trees or in their cars at harvest time.

Despite their poverty, workers in the U.S. earn three of four times what they do in Mexico, Velasco points out. But the cost of living north of the border is higher too. Migrants quickly begin measuring their earnings, as Muñoz Vasquez did, not in comparison to what they earned in Mexico, but to what it takes to live in the U.S. They can see themselves on the bottom compared also to the standard of living in the U.S. world surrounding them, sometimes falling below the legal minimum.

Even after a decade of activity, “the conditions haven’t changed at all,” Rufino concluded in the mid-90s. “The growers don’t obey the state and federal labor laws. They don’t pay the minimum wage, and sometimes workers are robbed of their wages entirely. People work on piece rate, where they get paid according to what they do. If they pay a dollar a bucket, and I pick 20 buckets in eight hours, they still just pay me $20, even though the law says I’m guaranteed the minimum wage, which (in 1996) would be $34.”

Rufino’s activity brought him into contact with other organizations of indigenous migrants, who were produced by the same flow of displaced people and painful political turmoil that was part of the migrant experience. Some, like Arturo Pimentel, were also militants, and shared with Benito Garcia and Rufino himself a political history on the left and in the PSUM. Rufino’s work organizing OPEO connected him with other indigenous organizers like Filemon Lopez in the Asociación Cívica de Benito Júarez, organized in Fresno in 1986. Sergio Mendez, Algimiro Morales, and others had organized migrants from Tlacotepec, first as the Comite Civico Popular Tlacotepense (closely tied to the PCM, according to Rivera Salgado), and then in the Comité Cívico Popular Mixteco in Vista. They had longstanding ties with the left across the border in Baja California.

Rufino got to know the Organizacion Regional de Oaxaca (ORO), started in 1988 in Los Angeles, where over 70,000 Zapotec migrants were concentrated. There ORO began organizing the Guelaguetza dance festival in Normandie Park, reproducing the festival in Oaxaca that every year showcases the dances of the state’s indigenous communities. By 1992 The ORO Guelaguetza featured 16 dances from all seven regions of Oaxaca, and for the first time in the U.S., the famous Danza de la Pluma. A decade later at least seven other Guelaguetza festivals had been organized in farm worker towns throughout California.

Laura Velasco argues that “the organizing traditions of these activists came together, which made it possible to mix the tactics and ideas of indigenous rural community organizing, the urban peoples’ movements and the class vision of the leftwing parties of the 80s, especially the PSUM. A new organizing space opened with the experience they’d gained in the fields of California. The conditions of work and displacement created the possibility for new alliances between peoples and ethnic groups.”

Velasco says that many of those organizations and their leaders participated in the first campaigns of Mexican political parties on the U.S. side of the border. In 1988 Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, a former governor of Michoacan who’d broken with the PRI, became the presidential candidate of the National Democratic Front. Earlier the PSUM had merged with another leftwing party to form the Mexican Socialist Party, and initially fielded its own presidential candidate, Heberto Castillo. When it appeared that Cardenas could beat the PRI, however, Castillo’s candidacy was withdrawn and they backed Cardenas instead.

Cardenas won, by all non-PRI accounts, but the government nevertheless declared the PRI’s Carlos Salinas de Gortari the victor after a fraudulent vote count. Afterwards the PSUM/Mexican Socialist Party merged with Cardenas supporters who’d broken from the PRI, and formed the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD). In the process, however, the original socialist ideology of the PCM and PSUM was gradually jettisoned. The PRD eventually became the governing party of Mexico City and several other Mexican states.

In Los Angeles, the four migrant organizations came together on October 5, 1991 and formed the Binational Mixteco/Zapoteco Front. “It then took off in 1992,” Rufino recalled, “when the governing bodies of the world were celebrating the famous 500 years of the discovering of the Americas. They said that Christopher Columbus was welcomed as a grand hero who brought good things. They wouldn’t talk about the massacres or the genocide in our villages. All the indigenous organizations on the American continent protested against this celebration.

“We wanted to tell a different story — that our people were stripped of our culture. They imposed a different God on us, and told us that nature wasn’t worth anything. In reality nature gives us life. Our purpose was to dismantle the old stereotypes, to march, to protest. Afterwards we thought, why not keep organizing for human rights, labor rights, housing, and education?”

Academics began taking note of this growing wave of activism. David Runsten, Carol Zabin and Michael Kearney at the University of California made one of the first surveys of indigenous farm workers in California, showing that settlements in the U.S. were linked to hometowns in Oaxaca, and to other settlements in Baja California. In 1992 Don Villarejo and the California Institute for Rural Studies published a report criticizing California Rural Legal Assistance, the legal aid organization for the state’s farm workers, for not paying attention to this demographic change.

Jose Padilla, CRLA’s director, and Claudia Smith, a CRLA attorney in San Diego, organized a conference to talk about the challenge of providing legal services to farm workers in Mixteco, Triqui and other indigenous languages. Most of the activists urging CRLA to respond, including Rufino, Pimentel, Morales and others, came from the organizations that had formed the Frente Mixteco/Zapoteco. “I knew right away that we needed to hire Rufino, to ensure that we had a strong connection to the leadership of this movement,” says Padilla.

Eventually other Frente members also went to work for CRLA as community outreach workers. Rufino was the first. It was his first step out of the fields, and gave him the opportunity to do political and labor rights work full time. In one of their first battles, Rufino and CRLA fought Chevron Corporation over a toxic dump beneath a trailer park inhabited by families from San Miguel Cuevas, and forced the company to pay several million dollars to resettle them.

Rufino also tried to negotiate a cooperative relationship with the United Farm Workers in the same period, but with much less success. “We recognized that the UFW is a strong union representing agricultural workers. They in turn recognized us as an organization that tries to gain rights for indigenous migrants. Even within the UFW, though, some people said that indigenous people were ‘rompehuelgistas’ [strikebreakers] or ‘esquiroles’ [scabs]. In ‘84 there was a strike in Merced, and we were called these names. But the people from the union only spoke to us in Spanish. They didn’t understand that our people only spoke Mixteco or Zapoteco, so many times, because of the language barrier, we couldn’t understand each other. This treatment doesn’t live up to the political ideals of the union. They should welcome indigenous people, and be more open-minded. In reality, although we felt the union didn’t take us seriously, that campaign was historic because the union finally recognized us in a formal way.”

After the relationship foundered, the UFW mounted a long campaign in the late 1990s to organize strawberry workers in Watsonville, a large percentage of whom are from Oaxaca. There the union suffered from its lack of a more organic connection to indigenous communities. At the same time, Mixteco leader Jesus Estrada and a handful of others organized a strike of strawberry workers in Santa Maria. Those leaders were blacklisted, and no permanent organization emerged from that struggle. But in later years the UFW did develop a different relationship with indigenous workers. It fought immigration raids against the Triqui community in Greenfield, and hired Mixteco and Triqui community leaders there as organizers, even veterans of the teachers’ movement. Rufino and other leaders of the Frente Mixteco/Zapoteco, and the organization that grew out of it, continued to support strikes by Oaxacan workers in San Quintin and Washington State, although they didn’t organize them themselves.

The Birth and Growth of the Frente Indigena de Organizaciones Binacionales

In a conference in Tijuana in 1994 the Frente Mixteco/Zapoteco expanded to include people from other Oaxacan indigenous groups, such as Triquis and Chatinos, and renamed itself the Binational Indigenous Oaxacan Front (FIOB). “Three things made this possible,” Velasco says, “the implementation of the North American Free Trade Agreement, the Zapatista uprising with its demand for indigenous autonomy, and the imposition of Operation Guardian/Gatekeeper on the border in San Diego County.”

The Zapatista uprising on January 1, 1994, had a profound impact on indigenous Mexicans in the U.S. “The rise of the Zapatista army made it easier for the rise of many indigenous organizations in Mexico and in the whole continent – I would say the world,” Rufino said. “When the Zapatistas rose, the war lasted 8 days. We organized right away – here in California, in Oaxaca and Baja California – with hunger strikes, denouncing the government. When the Zapatistas were detained or their lives were threatened we picketed consulates in Fresno and Los Angeles to pressure the Mexican government. These simultaneous actions helped us realize that when there’s movement in Oaxaca there’s got to be movement in the U.S. also. We put that lesson to use later on, when our own leaders were attacked.

“The Zapatistas helped the mestizos to civilize themselves a little bit. They became more humane, recognizing that indigenous people are human. Afterwards we began to make advances in Mexico in rescuing our languages, and getting laws making it illegal to discriminate against indigenous people. Even outside the framework of the San Andres Accords, we have been able to propose a reform to the law protecting our right to indigenous culture. We are trying to create an institution of the indigenous languages of all of Mexico, not just Mixteco or Zapateco, but for the Purepecha, the Triqui, and the Tarahumara and Mayo people in Sonora, which would create written materials such as dictionaries, books and stories. In addition to Spanish, we want Mixteco, Zapoteco, Tarahumara and other languages taught in the schools, including to mestizos if they live in that region.”

The Zapatistas chose to start their uprising on January 1, 1994, because it was the day the North American Free Trade Agreement went into effect. They warned that the treaty, and the neoliberal development model it was reinforcing, would spell disaster for indigenous communities in Mexico. In the countryside, government policy favored large landholders producing for export, over small ones producing for a national market. That especially affected indigenous communities, which often hold land in common, as well as agricultural communities based on the ejidos established by earlier agrarian reform.

Oaxaca suffered more than most. It is one of the poorest states in Mexico, where the government category of extreme poverty encompasses 75 percent of its 3.4 million residents, according to Servicios Para una Educación Alternativa A.C. (EDUCA). A 2005 study by Ana Margarita Alvarado Juarez published by the Institute for Sociological Investigation of the Autonomous University Benito Juarez of Oaxaca, called “Migration and Poverty in Oaxaca,” says Oaxaca consistently falls far below the national average for every measure of poverty and lack of development.

She cites data by the National Council of Population (CONAPO), that while nationally 9.4% of Mexico’s people are illiterate, in Oaxaca 21.5% are. Nationally 28.4% of students don’t finish elementary school, but in Oaxaca 45.5%, almost half, never complete it. Nationally 4.8% of Mexicans live with no electricity, 11.2% live in homes with no running water, and 14.8 percent walk on dirt floors. In Oaxaca, the numbers are more than double – 12.5%, 26.9% and 41.6% respectively. Only in Chiapas, Mexico’s poorest state, do children get less schooling then Oaxaca’s average of 6.9 years per person.

Displacement of people from Oaxacan communities tracks the growth in poverty. In 1990 the net out migration from Oaxaca was 527,272 (people leaving minus people arriving or returning). In 2000 that number grew to 662, 704. In the five years between 2000 and 2005, despite a high birthrate, Oaxaca’s population only grew 0.39%. Eighteen percent of its people have left for other parts of Mexico and the U.S. Oaxacan migration was part of a much larger movement of people. In 1990 4.5 million Mexican migrants lived in the U.S. By 2008 that number had mushroomed to 12.7 million – a little less than 10% of Mexico’s entire population.

“There are no jobs, and NAFTA made the price of corn so low that it’s not economically possible to plant a crop anymore,” Rufino charged in an interview in 2004. “We come to the U.S. to work because we can’t get a price for our product at home. There’s no alternative. We know the reasons we have to leave. Over 5000 of us have died trying to cross the border in the last decade.”

As Velasco points out, the rising death toll on the border, and the impact of increasing immigration enforcement, including the construction of prisons (“detention centers”) for deportees, had a big impact on indigenous migrants, because of their widespread lack of status. That produced a sense of urgency among the organizations that came together to form the FIOB.

While it sought to build a base of indigenous members from Oaxaca, the FIOB was not a hometown association. In fact, OPEO itself disbanded. “If we have a committee just of people from San Miguel Cuevas, we can’t organize or go beyond it. In the organization of the FIOB, though, all of the communities are working together, to create consciousness, to educate, to orient, and all of the rest. That is the biggest difference,” Rufino explained.

And from the beginning, the FIOB consciously saw itself as a binational organization, and its members as people belonging to binational communities that span the border. Its presence grew, and subsequently several indigenous organizations from the states of Guerrero and Michoacan joined, resulting in a change of its name to the Indigenous Front of Binational Organizations in 2005. At the same time, almost as soon as it started in California, it began to organize back in Oaxaca itself, as well as in Oaxacan communities in Baja California. It set up a structure of local committees that belong to state organizations. Every three years, the FIOB chapters elect delegates to a binational assembly, who choose a binational governing committee, and a binational coordinator responsible to it.

Those triennial assemblies are held in Mexico. In part, this is a practical matter. Indigenous farmers can’t easily come up with the money to travel as delegates to meetings in the U.S. Even if they could, getting visas would be virtually impossible. U.S. consulates suspect that poor Oaxacans trying to visit California are just looking for a way to cross the border to stay and work. Consequently, the FIOB’s Mexican assemblies always draw far more delegates from Mexico than from the U.S. While the leaders of the FIOB in the 1990s came from the migrant organizations and movement in the U.S., its growth in Oaxaca has slowly been shifting the organization’s center of gravity, and its political activity, to the south.

Being accountable to decisions by its base communities is not just rhetoric. The FIOB’s first director, Juan Martinez, who’d been the coordinator of the Associacion Civica Benito Juarez, was removed because he organized a conference in Oaxaca without agreement from other leaders, and to make it worse, invited the governor of Oaxaca to participate. FIOB’s second director, Arturo Pimentel, was expelled for running for office in Oaxaca while refusing to give up his position as the FIOB binational coordinator (required by the bylaws) and for misappropriating the organization’s funds. Rufino was the FIOB’s third binational coordinator, from 2001 to 2008, and was followed by Gaspar Rivera Salgado. All were leaders of the FIOB and its predecessor organizations in California.

In 2011 Rivera Salgado stepped down, and his successor, Bernardo Ramirez, lived in the heart of the Mixteca region of Oaxaca. Ramirez worked five seasons in the fields of the United States, an experience shared with most FIOB delegates. His election, however, signaled that the organization’s center of gravity was moving more firmly into Mexico. Ramirez was followed by Romualdo Juan Gutierrez Cortez, the FIOB’s current binational coordinator, a teacher and former leader of the state’s teachers union.

From the beginning, one of the biggest problems the FIOB organizers faced was the participation of women. According to FIOB activist Irma Luna, “the subject of domestic violence is taboo in the Oaxaqueño community, but it happens often. “Many women are used to taking abuse. Divorce and separation are not options and they feel they have to stay in that environment,” Luna charges. She comes from San Miguel Cuevas, like Rufino, although she was born when her parents were working in Sinaloa. Rufino recruited her when she and her husband moved to Fresno, and encouraged her to resist losing her ability to speak Mixteco. Luna followed Rufino in going to work for CRLA, and he asked her to organize a FIOB program to stop domestic violence.

“After I began to work in the domestic violence team, I noticed that when I spoke about it, people would slowly leave the room,” she recalled in Communities Without Borders. “Others would ask why I was telling women to call the police on their husbands. When I would go to the radio station to talk about my project, listeners called to ask why I was giving this information to the women. It is a problem that goes back to Mexico, but there is a lot of pressure in the United States too. Immigration only adds to the domestic violence problem. But now there is more support in towns in Oaxaca for women to report their husbands, and many women send their husbands to jail after receiving a brutal beating.

“Now I am a community worker and help people working in farm labor. When they don’t have portable bathrooms, or if their employer refuses to pay them their wages, I go the worksite and investigate. I knew I wasn’t going to be a woman that would just stay at home and have about ten children and wait to see what life imposed on me.”

Oralia Maceda showed up in California in 1998, when she was 22, planning to stay a month. She’d worked in the FIOB office in Oaxaca, but complained that she had to ask permission from its director, Arturo Pimentel, before she could do anything. Gaspar Rivera Salgado brought her into the Fresno office where she met Rufino. “Rufino asked me if I was interested in working with women, and I agreed,” she recalled. “At first there were few women involved in FIOB. Rufino asked me to share my experiences in Oaxaca, and we started going to different cities – Fresno, Selma, Santa Maria, and Santa Rosa. He was always doing something and he never got tired. It motivated me to see him going.”

Rufino saw that Maceda had organizing skills, and tried to help her develop them. “In Oaxaca you are not allowed to go to the agency [local government office] and sit with the presidents, because you are a woman,” she charges. “Another issue was my age. I would advise older women how to care for their children and they would get upset. But thanks to Rufino’s support, in California I was able to do this work. As Mixteca women we created a calendar that showed our stories, and then we created a memory book. We tried to create a youth group. We organized a meeting in a ranch, and 20 young people participated. But sometimes only 2 or 3 people would show up for meetings I organized. When things went wrong I’d ask Rufino why he didn’t say anything first. He told me that if I have an idea I should go ahead with it, and if it went wrong I would learn from it, instead of him just telling me how to do things.

“Today, women sometimes participate more than men. Their biggest obstacle is the lack of time. They have to work in the fields, and take care of their families. They don’t have childcare. I believe men have to be more conscious of women’s needs, so they can participate. But right now there is room for women and their ideas to develop.”

Odilia Romero, who anchored FIOB in Los Angeles, was elected the first woman as binational coordinator at the March 2018 assembly in Huajuapan, Oaxaca. Romero and Rufino worked closely together from the organization’s first years. Brought by her parents from San Bartolome Zoogocho, she witnessed as a child the town’s depopulation – the formative experience of thousands of Oaxacan migrants. “In the 80s there were about a thousand people there,” she remembers. “Then we started leaving to the city of Oaxaca, and then to the U.S., until only 88 were people left. All of a sudden on a Thursday, for instance, people would leave, and us children were left behind.”

Maylei Blackwell. Associate Professor of Chicana & Chicano Studies and Gender Studies at UCLA, says Romero has a “rebellious spirit that has characterized her since childhood.” Blackwell recorded her oral history, in which Romero says, “my rebellion helps me to hope that a better society is possible.”

Before meeting Rufino Romero read an article he’d written about the FIOB. “It talked about how it started, and that some of its leaders were fired for corruption and negative actions towards the members,” she remembers. “I was very touched because I found what I was looking for. An organization that speaks of its triumphs and barriers is worthy of admiration.” Rufino encouraged her to join, and then to organize.

“We are not going to have Barbie positions here,” Romero declares. “The Frente is one of the few organizations that truly gives us space to talk about gender, with the intention of going from talk into action, so that women have a real role … We have to take up some of the good things of the indigenous peoples, of an egalitarian society, and implement it as an indigenous organization, but also talk about the things we do not like. One of the things we do not like is to exclude women.”

Rufino and FIOB members demonstrate at the Mexican consulate. Photo copyright © 2019 by David Bacon.

Laura Velasco worked with Romero and another woman in FIOB leadership, Centolia Maldonado, an activist in Oaxaca who developed the evidence that led to the expulsion of Arturo Pimentel. Maldonado herself was eventually expelled amid accusations of sexism among FIOB leaders (an accusation that Romero also made). Velasco says she’s still angry about it, “but Rufino always treated women in the organization with friendship and respect. He and Gaspar were among the few in a conflict clearly about sex who were ethical and sympathetic towards Maldonado. Both she and Romero were very important in Rufino’s development as a leader, and in the development of FIOB’s gender policy.”

The FIOB also organized its members in the U.S. to advocate for immigration reform. In its 2005 binational assembly the FIOB passed a resolution condemning guest worker programs. That set it apart from many migrant rights organizations in the U.S. at the time, many of whom were willing to accept new programs (supposedly with greater rights for migrants), in exchange for legalization for the undocumented. While Mexico’s government was also calling for the negotiation of a new bracero program, Rufino charged that “migrants need the right to work, but these workers don’t have labor rights or benefits. It’s like slavery.”

Gaspar Rivera Salgado, who guided the development of FIOB’s immigration program, connected migrant rights with the right to not migrate. “Both rights are part of the same solution,” he explained. “We have to change the debate from one in which immigration is presented as a problem to a debate over rights. The real problem is exploitation.” The FIOB position also emphasized language rights for migrant communities and respect for their indigenous culture.

Organizing for immigrant rights was more than taking a political position; it was part of building the FIOB’s membership base. In the early 2000s, Lorenzo Oropeza, a FIOB activist who also worked for CRLA, organized a chapter among a group of Triqui farm workers living out of doors in the reeds beside the Russian River in Sonoma County. Fausto Lopez, the group’s leader, explained, “I joined the FIOB because Lorenzo speaks my native language. He is Mixteco and we are Triqui, but he works with all Oaxaqueños. Since we’re from the same state we’re all the same. Then our local group elected me to represent them. I traveled to various parts of California with Lorenzo and met with other leaders. A lot of us farm workers don’t know our rights, and the FIOB teaches us. We also work for amnesty for immigrants, because so many of us cross the border illegally and so many die in the process.”

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.