THE LAND IS OUR LIFE

My revolutionary identity

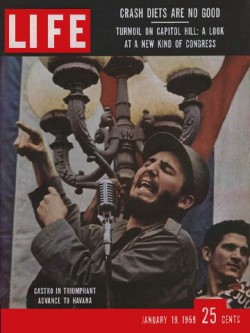

I was only five years old when the Cuban Revolution triumphed. We were aware of the national liberation movement and were amazed at learning that Fidel Castro, a lawyer, had entered Havana from the Sierra Maestra, victorious in the guerrilla war that brought down the hated dictator Fulgencio Batista. On January 1, 1959 the radical transformation in Cuba began and changed our lives because, being children, we learned that social change for justice and liberty was possible. My grandfather was also a revolutionary lawyer, who fought against the Guatemalan dictator Jorge Ubico, and returned from exile with the triumphant October 1944 Revolution.

On January 1, 1959 the radical transformation in Cuba began and changed our lives because, being children, we learned that social change for justice and liberty was possible

My siblings and cousins felt the urgent need for justice and revolutionary change.

We loved the rebel cause and were inspired by “Chiqui” our activist aunt. The conditions of exploitation and oppression in Guatemala were comparable to those of Cuba. We knew that revolutionary struggle was indispensable and we dreamed of becoming guerrilleros. We lived through the photos of Life and Bohemia, admiring the greatness of the struggle and the certainty of its advance. It was thrilling when Chiqui, overcoming all the physical and security barriers, got to know “the bearded ones,” glowing with love and hope. These were the seeds of our militancy and determination.

These feelings came alive again when I visited the largest island in the Caribbean on a Food Sovereignty Tour organized by Food First in January of 2016. As a Food First representative I joined a group of twenty travelers, most of them from the US, on a ten day tour. We visited several agroecological farms in the provinces of Matanzas, Sancti Spritus, Villa Clara and Havana. During the tour we spoke openly, mostly with agro-ecologists, organized communities and public officials. I saw that each farm had its own personality, each provided lessons about people and agroecology, and were all amazing in their achievements. One of these farms made a deep impression on me: La Coincidencia, located in Matanzas.

Stay in the loop with Food First!

Get our independent analysis, research, and other publications you care about to your inbox for free!

Sign up today!Agricultural and artistic production is a passion

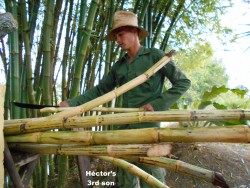

La Coincidencia farm is a creation of Hector Correa, his wife Odalys and their three children. Hector got his degree as an agronomist and then applied for and obtained free land from the Cuban government, and started growing food. They worked hard for 30 years to build a paradise! Odalys, an art historian, also values the land as a means of artistic and functional expression. Once she was on the farm, she learned ceramics and built an artist’s workshop. Presently the farm produces fruit, vegetables, legumes, pasture, sugar cane, honey, eggs, pork, poultry, beef, milk, cheese and ceramics. La Coincidencia’s agricultural and crafts production supports three families and feeds and employs fifteen more families.

Hector’s passion for agriculture and art is contagious. He welcomed the Food First group expressing his pleasure in sharing his work, products of his love and commitment. Hector shared his vision of how the person is created in the world: “The being was converted into a person when he sowed the first seed and was able to collaborate with himself in sustaining himself in nature, then he is a person because he acts with intention, visualizes the future and values what it permits him to produce.” Later he emphasized the principles that allowed them to build their farms: “Sacrifice, overcoming selfishness, enriching one’s self with every opinion and work and making art flow together with agriculture as a form of living and transcending.”

Under intermittent showers we got a tour of the farm, getting to know the areas where the various crops are planted. The small cane-brake has a manual mill where his children grind the sugarcane to offer us some cane juice – guarapo as the Cubans call it. Drinking the sweet liquid, Hector, with resignation, tells us they are suffering a heavy loss because the unseasonal rain and excessive heat of the preceding months that has led to premature flowering of the mango, guava and citrus trees. Now January’s wind and rains have knocked off the flowers from the trees. Two weeks ago, rain ruined the bean, yucca and malanga (a kind of sweet potato) harvest. But he kept his spirits up adding, “We shall come out of this fine in spite of the loss.” Throughout our visit Hector and Odalys conveyed their love, respect and deep commitment to Mother Earth.

The land represents economic, political and social power

The land is a means of production that allows us to produce food and various assets. Historically in the world, land and territory have been at the root of disputes because they represent economic, political and social power.

Before the Revolution, the land belonged to the plantation owners, US and other companies that produced monocultures, principally sugar, tobacco and coffee. After toppling the US-supported Batista dictatorship, the Revolution carried out three Agrarian Reforms in Cuba:

- The first Agrarian Reform in 1959 expropriated the large land-holdings. The State took part of the land and part was handed over to the peasants. The maximum size of a farm was 988 acres (400 hectares). The State continued producing monocultures with industrial agriculture supported by the Soviet Union (USSR). The peasants produced individually or in cooperatives.

- The second Agrarian Reform was in 1963, to eliminate the social class of land-owners that were exploiting the workers. The maximum size of the farm was reduced to 165 acres (67 hectares), and between 1963 and 1968 the ownership of State land increased from 60 to 82%. The State farms continued producing monocultures with salaried workers.

- In 1988 the government amended the Agrarian Reform with Decree 125, which regulated the possession, ownership and inheritance of the land agricultural resources. Then the State distributed 251,029 acres (101,588 hectares) of land.

- The third Agrarian Reform was in 1993; it redistributed land in usufruct to the workers; 60% of State land has been distributed.

- In 2008, another amendment provided for the acquisition of land in usufruct to whomever requests land for planting food.

In Cuba the land is available for every Cuban who wants to work it. Farmers are usually organized in cooperatives for agricultural and livestock production: Cooperatives of Agricultural Production (Cooperativa de Producción Agropecuaria or CPA), Cooperatives of Credit and Service (CCS) and Basic Units of Cooperative Production (UBPC). The UBPC’s were created with the third Agrarian Reform in 1993; it is an autonomous socio-economic community of agricultural and livestock production. Generally they continue with the same products produced when they were State farms, but now the land belongs to the farmers in usufruct. The farmers sign a production contract with the State, committing to produce a certain quantity of products which they market directly through the State at the established price. Farmers can sell excess harvests in farmers markets or to individual consumers at the going market price.

In Cuba the land is available for every Cuban who wants to work it.

In spite of the Agrarian Reforms and the promotion of agricultural and livestock production, in 2007 51% of Cuba’s arable land was unoccupied. To confront the problem of idle land, in 2008 Decree 259 gave land in usufruct for 10 years, renewable for 25 more years, to whomever had the ability and resources to make it produce. Someone without land can receive 33 acres (13.42 hectares) to begin with; someone with land that is fully producing can receive 99 more acres (30.26 hectares). The land is available to whomever commits to working it.

Throughout the world corporations and powerful national elites are evicting peasants from their lands. The land is the most precious asset and is seized violently by those who wield economic and political power, supported by the governments and the military. Small farms are disappearing as land concentrates in fewer and fewer greedy hands that produce money, not food; raping the land, contaminating it with chemicals with no concern about the quality of their production. It’s not like that in Cuba – the land is available to whomever wants to work it, but I noticed that the majority of young men and women do not want to work the land.

Complicated economic situation

It was interesting to note that the majority of the members of the cooperatives we visited were older persons, retirees. They explain that most of the younger generation do not want to work the land now, they try to move to the cities, they have academic degrees and aspire for another way of life. They also comment that many of the youth want to work in tourism or commerce where, so they think, it is easy to make money.

On the other hand, I learned that recently there have been a lot of economic changes made in Cuba; for example, any person can set up a private business—something that was prohibited before—and the private businesses catering to tourists are very popular. Another change is that starting in 2008, the dollar and the euro circulate freely and there are two kinds of national currency: the people’s Cuban peso—CUP, and the Cuban convertible peso—CUC (25 CUP = 1 CUC = US 0.86).

The creation of the two currencies was a government measure to unite (and manage) the foreign currencies circulating on the island. Before 1991, Cuba enjoyed favorable, subsidized trade with the Socialist Bloc. With the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba found itself with a deficit of foreign currency which forced the government to carry out profound economic, currency and market reforms. To protect its economy, the government created two forms of money and exchange. It keeps the CUP for salaries and the internal economy and uses the CUC for external commerce and tourism. This monetary reform complicated the economy overall, and Cubans without access to CUCs (or remittances in foreign exchange) are unhappy with it. Presently, the government is said to be working on a transition to unify its currencies.

Cuba has a planned socialist economy, the State possesses most of the means of production and employs 76% of the labor force (Prensa Latina, 2000). All capital investments are approved and regulated by the government. These measures —and free health, education and welfare services—erased the enormous economic disparities that existed before the Revolution. Cuba’s indices of human development (health, education, income, UN 2014) is superior to most Latin American countries, and surpass those of the US’s southern states. This has taken intense work and sacrifice on the part of the Cuban people. They have had to struggle against the US’s economic and financial blockade since 1960.

Any foreign product can be bought in the supermarkets with dollarized CUC; but you won’t find even basic products like a toothbrush in neighborhood shops. The regular salary of any worker is paid in CUP, but production incentives are paid in CUC. Agricultural producers have a production contract with the State that is paid in CUP, but they can sell their excess production in CUC. I confess I still don’t understand the economic situation. Some aspects seem contradictory to me.

Without the revolution it would have been impossible

To get a better understanding of this paradox, I spoke with my friend Sylvia, a Cuban professor of biochemistry who was 11 years old when the Revolution triumphed.

“The triumph of the Revolution filled us with great hopes that turned out into reality, the realization of our deepest hopes,” she said, “The first objective of the Revolution was health, education and justice for all of the Cuban people. We worked arduously and we achieved it. Our basic needs were satisfied, not to great excess but yes, with equity.

“I, as an orphan from birth, abandoned by my father and orphaned again by the death of my grandmother, was adopted by the Revolution. I had what was necessary to live, to educate myself and to become the woman, scientist and revolutionary. Without the Revolution this would have been impossible. But the youth of today did not know exploitation or oppression. They were born with their basic needs fulfilled, they take it for granted and they believe that it has always been this way.

“Reflecting with my compañeros, we realize that the Revolution failed. The Revolution did not present new challenges to the young, new aspirations, new reasons to struggle. Therefore, many young people have started to feel comfortable coopted, have been captivated by the consumerism and technology that exist outside of the island. Many young people now long for what is prohibited: to head for the United States. The rural life working the land is very hard, there are many limitations and few attractions, and the young have no reasons to struggle, nor do they have the dream of forging themselves into heroes.”

I can see that the Revolution has taken care of the present for the young people, but it does not offer attractive alternatives for the future. The migration from the countryside to the cities is happening throughout the world, for various reasons; it is and has been that way since the industrial revolution. It is happening rapidly in Cuba but the migration is more complicated because it is not in response to the lack of land nor the lack of a market for agricultural production. The Revolution still prioritizes agricultural workers and peasants. An agrarian program was carried out with health, education and organization, satisfying the basic needs of the rural population—something that cannot be compared with the miserable conditions of the rural communities in most Latin American countries. But these favorable conditions have not been able to keep the majority of the young people in the countryside, nor draw them back there. In Cuba the migration of young people and the abandonment of the land is a serious problem that threatens the national economy.

I can see that the Revolution has taken care of the present for the young people, but it does not offer attractive alternatives for the future.

During our visit we met with Juan Jose Leon Vega, Director of International Affairs of the Ministry of Agriculture. Juan Jose pointed out that the Ministry promotes livestock production: it provides the land, offers technical and organizational support and consumable goods and guarantees a market for what is produced. This answer shows that basic elements of production have been solved: the land and the market. But what happens with the labor force? How will Cuba confront this problem?

We can see that there is only one country in the world in which access to farm land is guaranteed – that country is Cuba. In the United States many young people want to get back to the countryside and work the land, but they can’t because the land is too expensive and because they have large student debts and high health care costs. In Latin America and other parts of the Third World people are returning to the countryside because they can’t find work in the cities. But they find no support there to be productive. Then, land grabs are violently evicting people from rural areas as well. It is ironic that Cubans have education, health care, free land and a guaranteed market, yet there are few young women and men that are willing to take the risk of building their future in the countryside, and to overcome the difficulties this implies. Change is coming fast – how will the young Cuban women and men defend their land?

EPILOGUE

In Old Havana on Los Mercaderes Street as I walked to meet our group I suddenly saw a statue that moved me deeply. It was a young sailor of mixed race, athletic and attractive. I drew closer and looked, I felt his strong presence saw his muscular hands radiate with energy. My eyes dwelt on every detail, until our faces met and I realized that it was a human statue. I felt my heart stop! In that statue I imagined the heartbeat of the Cuban youth: observing life, foreign, motionless, silent… perhaps committed to an intimate project, but without revealing itself in life as a global fact, like the communion of beings working in what is fundamental… change to survive, live and be sovereign.

I spoke in the statue’s ear, introducing myself, shared the reason for my trip, my love for the land and my commitment to food sovereignty. Then I expressed my deepest fear: if you young Cuban people do not take over the land and make it produce, international corporations will come and steal it, rape it, making you into slaves.

Somehow I felt that the young statue was inviting me to shake his hand. I shook his hand, pressing it hard to bid him my farewell. He pressed my hand in return and slowly raised it to his mouth. The young statue kissed my hand!

I hope that my words resonated in this young Cuban and that he repeats them, and that, as young people, Cubans recognize that their land, their territory belongs to them and that they are the ones called upon to produce, to be stewards of their own integral sovereignty.

REFERENCES

Funes, Fernando et al. Sustainable Agriculture and Resistance (Oakland: Food First Book, 2002).

Chan, May Ling & Eduardo Freyre Roach. 2012. Unfinished Puzzle Cuban Agriculture: Challenges, Lessons and Opportunities (Oakland: Food First Books, 2012).

BBC World News, Latin American & Caribbean, “Cuba to scarap two-currency system in latest reform.” October 22, 2013. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-24627620

Economist.com, “Double trouble.” October 23, 2013. http://www.economist.com/blogs/americasview/2013/10/cubas-currency

The Economist, “The comandante’s last move.” February 21, 2008. http://www.economist.com/node/10727899

EcuRed. “Unidades Básicas de Producción Cooperativa.” Accessed March 28, 2016. http://www.ecured.cu/Unidades_Básicas_de_Producción_Cooperativa

CubaEduca. “Primera Ley de Reforma Agraria.” Accessed March 28, 2016. http://historia.cubaeduca.cu/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3730%3Aprimer

La Guajirita, “May 11 – Finca Coincidencia,” June 17, 2014. https://miviajecubano.wordpress.com/2014/06/17/may-11-finca-coincidencia/

Wikiguate. “Alberto Paz y Paz.” February 27, 2015. http://wikiguate.com.gt/alberto-paz-y-paz/

Wikiguate. “Leonor Paz y Paz.” February 27, 2015. http://wikiguate.com.gt/leonor-paz-y-paz/

Part 1. My revolutionary identity

Part 2. Agricultural and artistic production is a passion

Part 3. The land represents economic, political and social power

Part 4. Complicated economic situation

Part 5. Without the revolution it would have been impossible

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.

Help Food First to continue growing an informed, transformative, and flourishing food movement.